Volume 22, Issue 2 (6-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(2): 28-32 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mirhosseini S, Vejdani H, Kordi Z, Khajeh M, Hosseini F S, Grimwood S, et al . Prolonged grief disorder and associated factors among Iranian general population. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (2) :28-32

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2002-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2002-en.html

Seyedmohammad Mirhosseini1

, Homa Vejdani2

, Homa Vejdani2

, Zahra Kordi3

, Zahra Kordi3

, Mahboobeh Khajeh4

, Mahboobeh Khajeh4

, Fatemeh Sadat Hosseini2

, Fatemeh Sadat Hosseini2

, Samuel Grimwood5

, Samuel Grimwood5

, Mohaddeseh Mohammadi2

, Mohaddeseh Mohammadi2

, Hossein Ebrahimi6

, Hossein Ebrahimi6

, Homa Vejdani2

, Homa Vejdani2

, Zahra Kordi3

, Zahra Kordi3

, Mahboobeh Khajeh4

, Mahboobeh Khajeh4

, Fatemeh Sadat Hosseini2

, Fatemeh Sadat Hosseini2

, Samuel Grimwood5

, Samuel Grimwood5

, Mohaddeseh Mohammadi2

, Mohaddeseh Mohammadi2

, Hossein Ebrahimi6

, Hossein Ebrahimi6

1- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran; Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran; Vice-Chancellery of Research and Technology, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

4- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran ,m_khajeh@ymail.com

5- Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

6- Center for Health Related Social and Behavioral Sciences Research, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

2- Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

3- Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Yazd, Iran; Vice-Chancellery of Research and Technology, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

4- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran ,

5- Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

6- Center for Health Related Social and Behavioral Sciences Research, Shahroud University of Medical Sciences, Shahroud, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 455 kb]

(616 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1674 Views)

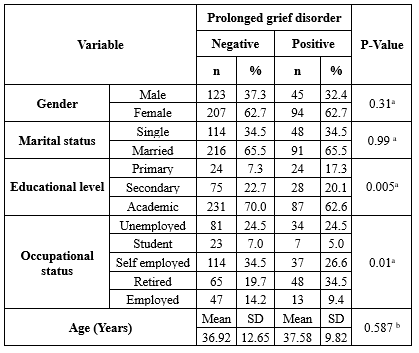

According to Table 2, there was a significant difference between the PGD-positive and PGD-negative groups in terms of educational level (p = 0.005) and occupational status (p = 0.01). The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of age, gender, or marital status.

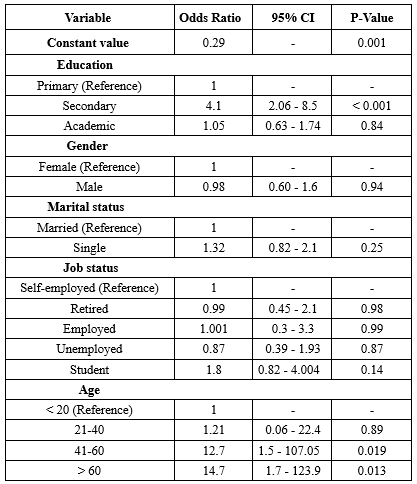

To control for confounding variables and to explore the association between PGD (A binary outcome) and all independent variables, a multivariate logistic regression model was used. Based on the backward elimination method, only variables with a statistically significant relationship with PGD were retained in the final model.

Discussion

This study provides important insights into the proportion and determinants of Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) within a general Iranian population. The reported proportion of PGD was notably high and the elevated mean score for prolonged grief symptoms indicates a substantial psychological burden for a significant portion of bereaved individuals. These findings are consistent with previous literature, which highlights the growing recognition of PGD as a global mental health concern with implications for healthcare planning and intervention strategies (11).

The study revealed significant sociodemographic differences between PGD-positive and PGD-negative individuals, particularly in terms of educational attainment and occupational status. Participants with only primary education were significantly more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for PGD. This aligns with prior research suggesting that lower educational attainment is associated with reduced health literacy, limited access to psychological coping strategies, and a lower likelihood of engaging with formal mental health services (17,20). Educational disadvantage may also restrict access to social resources and employment, compounding the emotional toll of bereavement.

Occupational status was similarly significant, with retired and unemployed individuals more prevalent in the PGD-positive group, while employed and self-employed individuals were more commonly represented in the PGD-negative group. Employment may provide protective factors such as routine, social interaction, and financial stability, which can help buffer against grief-related distress (21). Conversely, retirement particularly when unplanned or marked by isolation can exacerbate feelings of meaninglessness and loneliness, both of which are strongly associated with PGD (22).

The multivariate logistic regression analysis identified both age and educational level as significant predictors of PGD. Older individuals, particularly those over the age of 60, demonstrated significantly higher odds of meeting the criteria for PGD compared to younger participants. This is consistent with existing evidence that links advanced age to increased social isolation, greater exposure to cumulative losses, and reduced psychological flexibility (15,23).

Educational level remained a significant variable in the regression model even after adjusting for other factors. While initially unexpected, this may reflect deeper psychosocial mechanisms. Individuals with intermediate or lower education levels may experience more traditional or fatalistic beliefs about death, encounter greater barriers to accessing grief support, or rely on informal support systems that may not adequately address complicated grief reactions (24). These findings underscore the need for culturally and educationally tailored interventions.

Although not the primary focus, other factors such as gender, type of bereavement, and spirituality warrant attention. The study found a predominance of PGD among women, consistent with broader literature showing that women are more likely to express emotional distress and seek psychological help (23). However, this could also reflect underreporting or different grief expressions in men, necessitating more gender-sensitive assessment tools in future research.

The type of loss also influences grief trajectories. Research suggests that bereavement due to sudden events (e.g., accidents or cardiac arrest), prolonged illness (e.g., cancer), ambiguous loss (e.g., dementia), or traumatic deaths (e.g., suicide) each elicit distinct emotional and psychological responses (5,16,25). Unfortunately, this study did not differentiate between types of bereavement, representing a limitation and an area for future exploration.

Spirituality and religion are culturally embedded coping mechanisms. In Iranian and other Eastern cultures, religious rituals, communal mourning, and beliefs in the afterlife often provide a framework for resilience (26). For example, Mehdipour et al. found that spiritual-religious interventions significantly reduced complicated grief symptoms and enhanced psychological hardiness among bereaved mothers, underscoring the importance of culturally embedded coping mechanisms in Iranian society. Unfortunately, religion and spirituality information were not collected. Therefore, future studies should collect detailed demographic information, including religious affiliation and level of religious engagement, to assess potential differences in PGD risk and coping across religious and non-religious populations, as well as between different faith groups (26).

Future research should investigate the roles of loneliness, religiosity, and social support in moderating grief outcomes. It would also be worthwhile to compare the effectiveness of individual versus group psychotherapy for PGD. Group-based approaches may offer peer validation, collective meaning-making, and emotional normalization, which are especially relevant in collectivist cultures. This study provides an important starting point for developing such culturally informed, context-sensitive interventions.

Although the present study identifies age, education, and occupational status as significant predictors of PGD, broader psychosocial factors such as loneliness, religiosity, and social support have not yet been thoroughly investigated in the Iranian context, despite their well-documented relevance in other cultural settings. Preliminary studies suggest that loneliness and lack of emotional connection may intensify grief responses, particularly among bereaved youth and families affected by COVID-19 in Iran, who have described their grief as “inconsolable” and marked by helplessness and isolation (14,27).

Religiosity has also emerged as a protective factor in Iranian mental health research, with higher intrinsic religiosity linked to lower grief severity (26) and better psychosocial functioning in other populations, such as individuals with psychosis (28). These findings indicate that religious and spiritual frameworks may provide existential meaning, coping resources, and social support all of which are relevant to grief processing.

To date, however, there appear to be no published psychological interventions in Iran that specifically integrate these factors (i.e., loneliness, religiosity, and culturally specific forms of social support) into structured treatments for PGD. This represents a significant gap in the literature. Given the collectivist values and religious orientation of many Iranian communities, future interventions should incorporate faith-sensitive approaches, address social isolation, and consider group-based therapies to harness communal healing processes. Such interventions may be more culturally appropriate and effective than standard Western-developed models. Further research should examine how these psychosocial and cultural variables interact with PGD and evaluate the impact of tailored interventions on grief resolution in Iranian populations.

The present study has several limitations. First, it can be noted that it has a cross-sectional design. The authors recommend that future related studies be conducted using longitudinal designs. Given the localized sampling in a city in northeastern Iran, the generalizability of the study results is limited. Since self-report measures were used in the current study, the results may be subject to response bias. Furthermore, to increase the response rate, the assessment of other potential variables related to PGD was omitted. Therefore, it is recommended to evaluate other variables as potential correlates of PGD. Given the nature of the online sampling in the current study, the researchers assumed and relied on the honesty of the participants in responding to the forms and providing information on their own. However, due to the method of online sampling, there may be instances where this is beyond the researchers' control.

Conclusion

Prolonged grief disorder significantly impacts a considerable segment of the Iranian population, particularly among older adults and individuals with lower levels of educational attainment. Given the distinct distribution patterns across age groups and educational backgrounds in Iran, it is essential to implement multidisciplinary strategies for the prevention, management, and rehabilitation of at-risk individuals. These findings underscore the necessity for targeted mental health interventions and the development of culturally sensitive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches within the Iranian context. Future research should investigate the moderating roles of religiosity, loneliness, and social support in grief outcomes to inform comprehensive and culturally grounded care strategies.

Acknowledgement

This study was part of a research project approved by the Research Deputy of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Referral code: 14020077). We sincerely thank the participants and the Research Deputy of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences for their valuable support and contributions.

Funding sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participants’ rights to voluntary participation, protection from harm, the ability to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of their information. Informed consent-both verbal and written-was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The researchers are also committed to adhering to the ethical guidelines established by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) in the dissemination of study results. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Approval Code: IR.SHMU.REC.1402.189).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Study design: SM, HV, MK, HE; Data collection: SM, HV, FSH, MM; Data analysis: ZK; Study supervision: SM, MK; Manuscript writing: All authors (SM, HV, ZK, MK, FSH, SG, MM, HE). All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Full-Text: (258 Views)

Introduction

Grief is one of the most painful experiences in human life. It can happen after losing a loved one for any reason, such as illness, accidents, or natural disasters. Grief can affect a person physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially (1). After the death of someone close, most people go through a natural grieving process (2). Feelings such as sadness, anger, or guilt usually decrease within six months (3). However, some people may struggle to cope with the loss, and their grief becomes more severe and long-lasting. This condition is known as Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) (4). One major cause of PGD is the sudden and unexpected loss of a loved one, such as during natural disasters. These events can deeply affect the grieving process and make it harder for people to recover (5).

Losing someone is a common life experience around the world. While many people manage to adjust to their loss over time, others develop PGD. This condition is marked by strong and ongoing feelings of longing or being preoccupied with the person who has died. People with PGD may also feel that life has lost its meaning and struggle with changes in their sense of identity (6). PGD is now recognized as a mental health condition in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11, by the World Health Organization in 2018) and in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR, by the American Psychiatric Association in 2022) (7,8).

According to the DSM-5-TR, PGD is diagnosed when a person continues to experience strong grief for more than a year after the death (Or more than six months for children and teenagers). A person may feel deep sadness, longing, or constantly think about the person who passed away. These feelings happen almost every day and last for at least a month. The person may also have other symptoms, such as struggling with their identity, not believing the death has happened, avoiding reminders of the loss, feeling emotionally numb, finding it hard to return to daily life, feeling that life has no meaning, or feeling extremely lonely. These symptoms must cause real problems in daily life, work, or relationships. The grief must also be more intense and longer-lasting than what is normally expected in the person’s culture or religion. Also, the symptoms should not be caused by another mental health condition, substance use, or a medical problem (9).

Prevalence rates of PGD vary across populations and contexts. Studies have reported rates ranging from 8.5% to 35.5%, depending on cultural, demographic, and situational factors (10-13). Several factors have been identified as contributing to the risk of developing PGD, including the nature of the relationship with the deceased, the suddenness of the loss, lack of social support, history of mental illness, lower educational attainment, and cultural attitudes toward death and grief (14-17).

Understanding the factors that increase the risk of PGD is important. It can help health professionals like nurses and decision-makers plan support services for those in need. Given these findings, there is a pressing need to better understand PGD within different cultural settings. In Iran, few studies have examined the proportion and associated factors of PGD in the general population. Identifying the risk factors in this context can help healthcare professionals (Especially nurses and mental health providers) design more culturally appropriate screening, prevention, and support strategies.

Methods

Study design and settings

This cross-sectional study was conducted between October 2024 and March 2025 among 469 individuals from the general population in Shahroud, North east of Iran. Participants were selected using a convenience sampling method.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for this study were: the ability to use a smartphone to access the online questionnaire, a minimum level of literacy, being over 18 years of age, and having experienced the loss of a close loved one (Such as a spouse, parent, or child) at least 12 months prior to participation. Participants were excluded if they self-reported a psychiatric disorder or the use of neuroleptic medications. Measures were taken to prevent duplicate entries or responses submitted in an unreasonably short or long period of time. Data from six participants were excluded from the final analysis due to incomplete form responses.

Data collection

Data were collected through self-report using a demographic questionnaire and the Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-13-R). The survey tools were distributed to participants via a web link shared through city-wide information channels on social media platforms (Telegram and Eitaa social platforms). The main requirement for participation (In addition to other inclusion criteria) was to have experienced grief for more than 12 months, which was clearly stated in the online form for participants. Additionally, the number of months of grief experience was also evaluated to ensure more accurate screening. The demographic form included questions on age, gender, education level, occupation, marital status, relationship to the deceased, and cause of death.

The Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-13-R) is a tool developed by Prigerson et al. in 2021 to assess prolonged grief disorder (PGD), following a revision of the original PG-13 scale. The PG-13-R consists of 13 items, of which three (Items 1, 2, and 13) are used to determine diagnostic eligibility. These include questions about the loss of a loved one, the time elapsed since the death, and the individual’s functional impairment due to grief. The remaining 10 items (Items 3 to 12) assess grief symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). The scale is unidimensional, with total scores ranging from 10 to 50. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms of PGD (6). The validity of the PG-13-R in Iran was examined by Mirhosseini et al. (2024). Content validity was established using the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). All items met the minimum CVR threshold of 0.56 and were retained. The scale-level CVI (S-CVI) and CVR (S-CVR) were 0.99 and 0.85, respectively. Additionally, the modified Kappa coefficient for all items exceeded 0.7, indicating strong agreement among experts. Exploratory factor analysis using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLEFA) revealed a high Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.937, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 266.2236, p < 0.001), supporting the factorability of the data. One factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1 was extracted, accounting for 60.54% of the total variance. Both construct reliability and maximum reliability supported the scale's convergent validity. The internal consistency and stability of the scale were also high, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.935, McDonald’s omega of 0.938, and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.932 (18).

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the standard deviation of prolonged grief scores reported in a previous study. According to Sekowski et al. (2022), the standard deviation was 9.67. Using this value, and assuming a margin of error of 0.97 and a significance level of 0.05, the required sample size was estimated to be 475 participants, accounting for potential attrition (19).

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software (Version 26). Descriptive statistics (Frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential analyses (Multivariate logistic regression to identify predictors of prolonged grief disorder) were performed, with the significance level set at 0.05. Based on the review of the literature we conducted in this study, we reached the conclusion that a number of confounding factors affect our outcome, which is PGD (Prolonged Grief Disorder). Therefore, we initially analyzed the relationship between the confounding variables and the outcome using univariate analysis. Then, we included the variables with a p-value of less than 0.2 into a multivariate regression model. Finally, using the Backward model, only the variables that had a significant relationship remained in the model. The assumptions of logistic regression were confirmed in the following ways: 1-Our outcome variable is binary; in fact, the log-odds is a linear function. 2-The predictors are at the quantitative, binary, or categorical level. 3-There is no multicollinearity among the predictor variables.

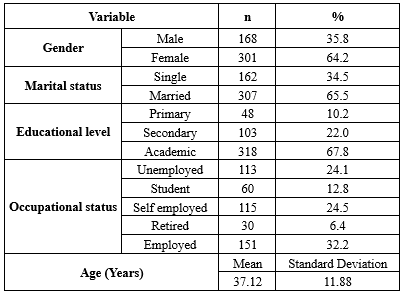

Results

Of the 469 participants in this study, 168 (35.8%) were male, and 307 (65.5%) were married, 115 (24.5%) were self-employed, and the mean age was 37.12 ± 11.88 years (Table 1).

Grief is one of the most painful experiences in human life. It can happen after losing a loved one for any reason, such as illness, accidents, or natural disasters. Grief can affect a person physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially (1). After the death of someone close, most people go through a natural grieving process (2). Feelings such as sadness, anger, or guilt usually decrease within six months (3). However, some people may struggle to cope with the loss, and their grief becomes more severe and long-lasting. This condition is known as Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) (4). One major cause of PGD is the sudden and unexpected loss of a loved one, such as during natural disasters. These events can deeply affect the grieving process and make it harder for people to recover (5).

Losing someone is a common life experience around the world. While many people manage to adjust to their loss over time, others develop PGD. This condition is marked by strong and ongoing feelings of longing or being preoccupied with the person who has died. People with PGD may also feel that life has lost its meaning and struggle with changes in their sense of identity (6). PGD is now recognized as a mental health condition in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11, by the World Health Organization in 2018) and in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR, by the American Psychiatric Association in 2022) (7,8).

According to the DSM-5-TR, PGD is diagnosed when a person continues to experience strong grief for more than a year after the death (Or more than six months for children and teenagers). A person may feel deep sadness, longing, or constantly think about the person who passed away. These feelings happen almost every day and last for at least a month. The person may also have other symptoms, such as struggling with their identity, not believing the death has happened, avoiding reminders of the loss, feeling emotionally numb, finding it hard to return to daily life, feeling that life has no meaning, or feeling extremely lonely. These symptoms must cause real problems in daily life, work, or relationships. The grief must also be more intense and longer-lasting than what is normally expected in the person’s culture or religion. Also, the symptoms should not be caused by another mental health condition, substance use, or a medical problem (9).

Prevalence rates of PGD vary across populations and contexts. Studies have reported rates ranging from 8.5% to 35.5%, depending on cultural, demographic, and situational factors (10-13). Several factors have been identified as contributing to the risk of developing PGD, including the nature of the relationship with the deceased, the suddenness of the loss, lack of social support, history of mental illness, lower educational attainment, and cultural attitudes toward death and grief (14-17).

Understanding the factors that increase the risk of PGD is important. It can help health professionals like nurses and decision-makers plan support services for those in need. Given these findings, there is a pressing need to better understand PGD within different cultural settings. In Iran, few studies have examined the proportion and associated factors of PGD in the general population. Identifying the risk factors in this context can help healthcare professionals (Especially nurses and mental health providers) design more culturally appropriate screening, prevention, and support strategies.

Methods

Study design and settings

This cross-sectional study was conducted between October 2024 and March 2025 among 469 individuals from the general population in Shahroud, North east of Iran. Participants were selected using a convenience sampling method.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for this study were: the ability to use a smartphone to access the online questionnaire, a minimum level of literacy, being over 18 years of age, and having experienced the loss of a close loved one (Such as a spouse, parent, or child) at least 12 months prior to participation. Participants were excluded if they self-reported a psychiatric disorder or the use of neuroleptic medications. Measures were taken to prevent duplicate entries or responses submitted in an unreasonably short or long period of time. Data from six participants were excluded from the final analysis due to incomplete form responses.

Data collection

Data were collected through self-report using a demographic questionnaire and the Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-13-R). The survey tools were distributed to participants via a web link shared through city-wide information channels on social media platforms (Telegram and Eitaa social platforms). The main requirement for participation (In addition to other inclusion criteria) was to have experienced grief for more than 12 months, which was clearly stated in the online form for participants. Additionally, the number of months of grief experience was also evaluated to ensure more accurate screening. The demographic form included questions on age, gender, education level, occupation, marital status, relationship to the deceased, and cause of death.

The Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-13-R) is a tool developed by Prigerson et al. in 2021 to assess prolonged grief disorder (PGD), following a revision of the original PG-13 scale. The PG-13-R consists of 13 items, of which three (Items 1, 2, and 13) are used to determine diagnostic eligibility. These include questions about the loss of a loved one, the time elapsed since the death, and the individual’s functional impairment due to grief. The remaining 10 items (Items 3 to 12) assess grief symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). The scale is unidimensional, with total scores ranging from 10 to 50. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms of PGD (6). The validity of the PG-13-R in Iran was examined by Mirhosseini et al. (2024). Content validity was established using the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). All items met the minimum CVR threshold of 0.56 and were retained. The scale-level CVI (S-CVI) and CVR (S-CVR) were 0.99 and 0.85, respectively. Additionally, the modified Kappa coefficient for all items exceeded 0.7, indicating strong agreement among experts. Exploratory factor analysis using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLEFA) revealed a high Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.937, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 266.2236, p < 0.001), supporting the factorability of the data. One factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1 was extracted, accounting for 60.54% of the total variance. Both construct reliability and maximum reliability supported the scale's convergent validity. The internal consistency and stability of the scale were also high, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.935, McDonald’s omega of 0.938, and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.932 (18).

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on the standard deviation of prolonged grief scores reported in a previous study. According to Sekowski et al. (2022), the standard deviation was 9.67. Using this value, and assuming a margin of error of 0.97 and a significance level of 0.05, the required sample size was estimated to be 475 participants, accounting for potential attrition (19).

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software (Version 26). Descriptive statistics (Frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential analyses (Multivariate logistic regression to identify predictors of prolonged grief disorder) were performed, with the significance level set at 0.05. Based on the review of the literature we conducted in this study, we reached the conclusion that a number of confounding factors affect our outcome, which is PGD (Prolonged Grief Disorder). Therefore, we initially analyzed the relationship between the confounding variables and the outcome using univariate analysis. Then, we included the variables with a p-value of less than 0.2 into a multivariate regression model. Finally, using the Backward model, only the variables that had a significant relationship remained in the model. The assumptions of logistic regression were confirmed in the following ways: 1-Our outcome variable is binary; in fact, the log-odds is a linear function. 2-The predictors are at the quantitative, binary, or categorical level. 3-There is no multicollinearity among the predictor variables.

Results

Of the 469 participants in this study, 168 (35.8%) were male, and 307 (65.5%) were married, 115 (24.5%) were self-employed, and the mean age was 37.12 ± 11.88 years (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Demographic information of participants (N =469)

|

According to Table 2, there was a significant difference between the PGD-positive and PGD-negative groups in terms of educational level (p = 0.005) and occupational status (p = 0.01). The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of age, gender, or marital status.

To control for confounding variables and to explore the association between PGD (A binary outcome) and all independent variables, a multivariate logistic regression model was used. Based on the backward elimination method, only variables with a statistically significant relationship with PGD were retained in the final model.

|

Table 2. Prolonged grief disorder according to demographic characteristics

a: Chi-square, b: Independent t-test, SD: Standard Deviation |

|

Table 3. The role of independent variables related to prolonged grief disorder in the logistic regression model

CI: Confidence Interval |

Discussion

This study provides important insights into the proportion and determinants of Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) within a general Iranian population. The reported proportion of PGD was notably high and the elevated mean score for prolonged grief symptoms indicates a substantial psychological burden for a significant portion of bereaved individuals. These findings are consistent with previous literature, which highlights the growing recognition of PGD as a global mental health concern with implications for healthcare planning and intervention strategies (11).

The study revealed significant sociodemographic differences between PGD-positive and PGD-negative individuals, particularly in terms of educational attainment and occupational status. Participants with only primary education were significantly more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for PGD. This aligns with prior research suggesting that lower educational attainment is associated with reduced health literacy, limited access to psychological coping strategies, and a lower likelihood of engaging with formal mental health services (17,20). Educational disadvantage may also restrict access to social resources and employment, compounding the emotional toll of bereavement.

Occupational status was similarly significant, with retired and unemployed individuals more prevalent in the PGD-positive group, while employed and self-employed individuals were more commonly represented in the PGD-negative group. Employment may provide protective factors such as routine, social interaction, and financial stability, which can help buffer against grief-related distress (21). Conversely, retirement particularly when unplanned or marked by isolation can exacerbate feelings of meaninglessness and loneliness, both of which are strongly associated with PGD (22).

The multivariate logistic regression analysis identified both age and educational level as significant predictors of PGD. Older individuals, particularly those over the age of 60, demonstrated significantly higher odds of meeting the criteria for PGD compared to younger participants. This is consistent with existing evidence that links advanced age to increased social isolation, greater exposure to cumulative losses, and reduced psychological flexibility (15,23).

Educational level remained a significant variable in the regression model even after adjusting for other factors. While initially unexpected, this may reflect deeper psychosocial mechanisms. Individuals with intermediate or lower education levels may experience more traditional or fatalistic beliefs about death, encounter greater barriers to accessing grief support, or rely on informal support systems that may not adequately address complicated grief reactions (24). These findings underscore the need for culturally and educationally tailored interventions.

Although not the primary focus, other factors such as gender, type of bereavement, and spirituality warrant attention. The study found a predominance of PGD among women, consistent with broader literature showing that women are more likely to express emotional distress and seek psychological help (23). However, this could also reflect underreporting or different grief expressions in men, necessitating more gender-sensitive assessment tools in future research.

The type of loss also influences grief trajectories. Research suggests that bereavement due to sudden events (e.g., accidents or cardiac arrest), prolonged illness (e.g., cancer), ambiguous loss (e.g., dementia), or traumatic deaths (e.g., suicide) each elicit distinct emotional and psychological responses (5,16,25). Unfortunately, this study did not differentiate between types of bereavement, representing a limitation and an area for future exploration.

Spirituality and religion are culturally embedded coping mechanisms. In Iranian and other Eastern cultures, religious rituals, communal mourning, and beliefs in the afterlife often provide a framework for resilience (26). For example, Mehdipour et al. found that spiritual-religious interventions significantly reduced complicated grief symptoms and enhanced psychological hardiness among bereaved mothers, underscoring the importance of culturally embedded coping mechanisms in Iranian society. Unfortunately, religion and spirituality information were not collected. Therefore, future studies should collect detailed demographic information, including religious affiliation and level of religious engagement, to assess potential differences in PGD risk and coping across religious and non-religious populations, as well as between different faith groups (26).

Future research should investigate the roles of loneliness, religiosity, and social support in moderating grief outcomes. It would also be worthwhile to compare the effectiveness of individual versus group psychotherapy for PGD. Group-based approaches may offer peer validation, collective meaning-making, and emotional normalization, which are especially relevant in collectivist cultures. This study provides an important starting point for developing such culturally informed, context-sensitive interventions.

Although the present study identifies age, education, and occupational status as significant predictors of PGD, broader psychosocial factors such as loneliness, religiosity, and social support have not yet been thoroughly investigated in the Iranian context, despite their well-documented relevance in other cultural settings. Preliminary studies suggest that loneliness and lack of emotional connection may intensify grief responses, particularly among bereaved youth and families affected by COVID-19 in Iran, who have described their grief as “inconsolable” and marked by helplessness and isolation (14,27).

Religiosity has also emerged as a protective factor in Iranian mental health research, with higher intrinsic religiosity linked to lower grief severity (26) and better psychosocial functioning in other populations, such as individuals with psychosis (28). These findings indicate that religious and spiritual frameworks may provide existential meaning, coping resources, and social support all of which are relevant to grief processing.

To date, however, there appear to be no published psychological interventions in Iran that specifically integrate these factors (i.e., loneliness, religiosity, and culturally specific forms of social support) into structured treatments for PGD. This represents a significant gap in the literature. Given the collectivist values and religious orientation of many Iranian communities, future interventions should incorporate faith-sensitive approaches, address social isolation, and consider group-based therapies to harness communal healing processes. Such interventions may be more culturally appropriate and effective than standard Western-developed models. Further research should examine how these psychosocial and cultural variables interact with PGD and evaluate the impact of tailored interventions on grief resolution in Iranian populations.

The present study has several limitations. First, it can be noted that it has a cross-sectional design. The authors recommend that future related studies be conducted using longitudinal designs. Given the localized sampling in a city in northeastern Iran, the generalizability of the study results is limited. Since self-report measures were used in the current study, the results may be subject to response bias. Furthermore, to increase the response rate, the assessment of other potential variables related to PGD was omitted. Therefore, it is recommended to evaluate other variables as potential correlates of PGD. Given the nature of the online sampling in the current study, the researchers assumed and relied on the honesty of the participants in responding to the forms and providing information on their own. However, due to the method of online sampling, there may be instances where this is beyond the researchers' control.

Conclusion

Prolonged grief disorder significantly impacts a considerable segment of the Iranian population, particularly among older adults and individuals with lower levels of educational attainment. Given the distinct distribution patterns across age groups and educational backgrounds in Iran, it is essential to implement multidisciplinary strategies for the prevention, management, and rehabilitation of at-risk individuals. These findings underscore the necessity for targeted mental health interventions and the development of culturally sensitive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches within the Iranian context. Future research should investigate the moderating roles of religiosity, loneliness, and social support in grief outcomes to inform comprehensive and culturally grounded care strategies.

Acknowledgement

This study was part of a research project approved by the Research Deputy of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Referral code: 14020077). We sincerely thank the participants and the Research Deputy of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences for their valuable support and contributions.

Funding sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participants’ rights to voluntary participation, protection from harm, the ability to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of their information. Informed consent-both verbal and written-was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The researchers are also committed to adhering to the ethical guidelines established by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) in the dissemination of study results. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Approval Code: IR.SHMU.REC.1402.189).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

Study design: SM, HV, MK, HE; Data collection: SM, HV, FSH, MM; Data analysis: ZK; Study supervision: SM, MK; Manuscript writing: All authors (SM, HV, ZK, MK, FSH, SG, MM, HE). All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Psychology and Psychiatry

References

1. Shear MK. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-60. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Guldin M-B, Leget C. The integrated process model of loss and grief-An interprofessional understanding. Death Stud. 2024;48(7):738-52. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Kustanti CY, Jen HJ, Chu H, Liu D, Chen R, Lin HC, et al. Prevalence of grief symptoms and disorders in the time of COVID‐19 pandemic: A meta‐analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2023;32(3):904-16. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Hilberdink CE, Ghainder K, Dubanchet A, Hinton D, Djelantik AMJ, Hall BJ, et al. Bereavement issues and prolonged grief disorder: A global perspective. Glob Ment Health (Camb). 2023;10:e32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Doering BK, Barke A, Vogel A, Comtesse H, Rosner R. Predictors of prolonged grief disorder in a German representative population sample: Unexpectedness of bereavement contributes to grief severity and prolonged grief disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:853698. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Prigerson HG, Boelen PA, Xu J, Smith KV, Maciejewski PK. Validation of the new DSM‐5‐TR criteria for prolonged grief disorder and the PG‐13‐Revised (PG‐13‐R) scale. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):96-106. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Carneiro Almeid MS, de Sousa Filho LF, Rabello PM. World Health Organization. International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). 2018 Feb 4 [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

8. Eisma MC. Prolonged grief disorder in ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR: Challenges and controversies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(7):944-51. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Boelen PA, Lenferink LI. Prolonged grief disorder in DSM-5-TR: Early predictors and longitudinal measurement invariance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2022;56(6):667-74. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, Farver-Vestergaard I, O'Connor M. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;212:138-49. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Yuan M-D, Wang Z-Q, Fei L, Zhong B-L. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder and its symptoms in Chinese parents who lost their only child: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1016160. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Yi X, Gao J, Wu C, Bai D, Li Y, Tang N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved survivors seven years after the Wenchuan earthquake in China: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2018;5(2):157-61. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Zhou N, Wen J, Stelzer E-M, Killikelly C, Yu W, Xu X, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of prolonged grief disorder in Chinese parents bereaved by losing their only child. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112766. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Asgari M, Ghasemzadeh M, Alimohamadi A, Sakhaei S, Killikelly C, Nikfar E. Investigation into Grief Experiences of the Bereaved during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Omega (Westport). 202315:302228231173075. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Boelen PA, Lenferink LIM. Symptoms of prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, and depression in recently bereaved people: Symptom profiles, predictive value, and cognitive behavioural correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(6):765-77. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Jordan JR, McIntosh JL. Grief after suicide: Understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors: Routledge. 2011. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

17. Buur C, Zachariae R, Komischke-Konnerup KB, Marello MM, Schierff LH, O'Connor M. Risk factors for prolonged grief symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2024;107:102375. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Mirhosseini S, Khajeh M, Sharif-Nia H, Hosseini FS, Ebrahimi H. Psychometric Properties of the Revised Version of the Prolonged Grief Disorder Scale (PG-13-R): A Methodological Study in the Iranian Population. Omega (Westport). 2024:00302228241272579. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Sekowski M, Prigerson HG. Associations between symptoms of prolonged grief disorder and depression and suicidal ideation.Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(4):1211-8. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: A decade on. Omega (Westport). 2010;61(4):273-89. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Paoletti J, Chen MA, Wu-Chung EL, Brown RL, LeRoy AS, Murdock KW, et al. Employment and family income in psychological and immune outcomes during bereavement. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2023;150:106024. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, Monterosso L, Halkett GKB, Davies A. Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 2010;34(8):673-98. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Djelantik AMJ, Smid GE, Kleber RJ, Boelen PA. Early indicators of problematic grief trajectories following bereavement. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018;8(sup6):1423825. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Harrop E, Goss S, Farnell D, Longo M, Byrne A, Barawi K, et al. Support needs and barriers to accessing support: Baseline results of a mixed-methods national survey of people bereaved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med. 2021;35(10):1985-97. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. Bağcaz A, Kılıç C. Differential correlates of prolonged grief and depression after bereavement in a population‐based sample. J Trauma Stress. 2024;37(2):231-42. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Mehdipour F, Arefnia R, Zarei E, Zarei EZ. Effects of spiritual-religion interventions on complicated grief syndrome and psychological hardiness of mothers with complicated grief disorder. Health Spiritual Med Ethics. 2020;7(2):20-6. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

27. Bashkoh M, Shahabzadeh S. The effect of mourning for parents affected by Covid 19 on the mental health of children and adolescents in Tehran (Case study). Biquarterly Journal of studies and Psychological news in Adolescents and Youth. 2021;2(1):25-32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

28. Djordjevic M, Farhang S, Shirzadi M, Mousavi SB, Bruggeman R, Malek A, et al. Self-stigma, religiosity, and perceived social support in people with recent-onset psychosis in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Associations with symptom severity and psychosocial functioning. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2024;70(3):542-53. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |