Volume 22, Issue 3 (9-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(3): 8-13 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Aghahosseini S S, Karami M, Rassouli M, Akbari M E, Ebrahimi H, Najafi K. Impact of palliative care on the quality of life and patient satisfaction in cancer patients: A before-and-after quasi-experimental study. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (3) :8-13

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2052-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2052-en.html

Shima Sadat Aghahosseini1

, Maryam Karami2

, Maryam Karami2

, Maryam Rassouli3

, Maryam Rassouli3

, Mohammad Esmaeil Akbari3

, Mohammad Esmaeil Akbari3

, Hamideh Ebrahimi4

, Hamideh Ebrahimi4

, Kazem Najafi5

, Kazem Najafi5

, Maryam Karami2

, Maryam Karami2

, Maryam Rassouli3

, Maryam Rassouli3

, Mohammad Esmaeil Akbari3

, Mohammad Esmaeil Akbari3

, Hamideh Ebrahimi4

, Hamideh Ebrahimi4

, Kazem Najafi5

, Kazem Najafi5

1- Lahore School of Nursing, The University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

2- Department of Medical-Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Cancer Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Lahore School of Nursing, The University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan ,hamideebrahimi363@yahoo.com

5- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran

2- Department of Medical-Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing & Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Cancer Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Lahore School of Nursing, The University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan ,

5- Department of Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Bam University of Medical Sciences, Bam, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 445 kb]

(888 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2259 Views)

Discussion

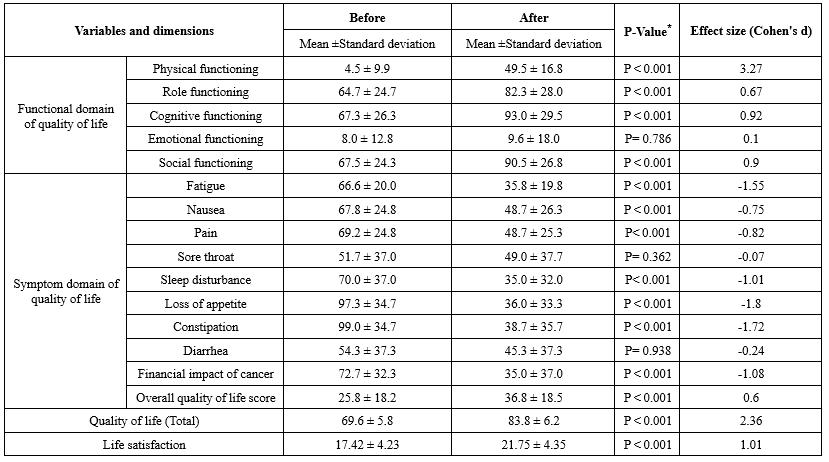

This study investigated the effect of a palliative care intervention on the quality of life and satisfaction among patients with cancer. The results showed significant improvement in patients' quality of life, except for emotional functioning, sore throat, and diarrhea.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the quality of life in palliative care. Nevertheless, the topic has been examined from various viewpoints, and there is no thorough evaluation of the available evidence. Additionally, the role of health-related quality of life in terminal or permanently disabling illnesses, which are among the leading causes of distress and reduced quality of life, remains controversial. Patients are often referred to palliative care when curative treatment is no longer effective (27). In this regard, a study's findings showed that palliative care improves the quality of life for patients with severe, end-stage illnesses at the end of life. Palliative care services reduce patient symptoms and eliminate the need for unnecessary medical interventions and imaging, thereby enhancing the quality of life for patients and their families compared to non-palliative care units (28). A study conducted in Indonesia demonstrated that the intervention resulted in significant improvements in emotional and social functioning, as well as alleviations in pain, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, and financial difficulties among patients (29). The findings of a meta-review by Demuro et al. (2024), which examined 14 systematic reviews, confirmed the effectiveness of palliative care interventions for patients with end-stage conditions or permanent disabilities (27). These findings align with previous evidence supporting the benefits of nurse-led palliative care programs in enhancing the physical, psychological, and emotional well-being of patients with advanced illnesses (30,31).

The current study further enhances understanding by implementing a culturally adapted model within Iran's healthcare system, where palliative care remains in its developmental phase. In Iran, the delivery of palliative care faces several systemic challenges, including insufficient nurse training, lack of infrastructure, and cultural taboos surrounding death and end-of-life conversations (32,33). Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that structured, culturally sensitive care provided by trained nurses under professional supervision can lead to significant improvements in patient outcomes. This suggests a practical pathway for expanding palliative services, even in resource-constrained hospital settings.

Findings regarding life satisfaction suggest that palliative care services have a positive impact on the life satisfaction of cancer patients. Measuring patient satisfaction with the services provided by the care team is crucial for evaluating the quality-of-care outcomes. This measurement offers valuable insights into patients’ experiences with these services, assesses their treatment adherence, identifies structural weaknesses, and evaluates the performance of the care team (34). A study conducted in Egypt, which assessed elderly patients’ satisfaction with palliative care services for cancer, revealed that 42% of patients were indifferent to the quality of palliative care, and 47% expressed moderate satisfaction with healthcare providers. These findings differ from those of the present study (35). This discrepancy may be attributed to cultural differences, the study population, and the training and experience of the palliative care team. In another study conducted in Bangladesh, which evaluated patient satisfaction with palliative care, over 88% of patients were satisfied with the services provided by the care team. The leading indicators of satisfaction in this study included assessment of physical symptoms, information on pain management, inclusion of family members in decision-making, coordination of care among healthcare providers, and the availability of physicians (34).

Although patient satisfaction with healthcare services is a key indicator of care quality, it is worth noting that life satisfaction is a broader and more complex concept. Life satisfaction encompasses various domains, including physical health, psychological well-being, social support, spiritual fulfillment, and the individual’s sense of purpose. While the quality of care received can influence life satisfaction, it is only one of many contributing factors. Therefore, studies that focus exclusively on patient satisfaction with care services may not fully capture the multidimensional nature of life satisfaction. In this study, the observed improvements in life satisfaction may reflect the cumulative impact of symptom relief, emotional support, family engagement, and culturally relevant education provided through the structured palliative care intervention.

One limitation of the study was the potential impact of patients' knowledge, previous experiences, motivation, and interest on the outcomes. Additionally, individual differences and the mental and emotional states of the patients at the time of completing the questionnaire may have influenced the program's implementation. These factors were beyond the researchers' control. Furthermore, the study's generalizability was limited by its quasi-experimental design and the use of convenience sampling from a single hospital in Tehran. The findings may not apply to the broader population of cancer patients in Iran or other cultural contexts. Future research utilizing randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs and multi-center sampling could enhance the external validity of the results. Other limitations of the study include the duration of the intervention and the follow-up period. Various factors influence quality of life and life satisfaction, and the results from the educational intervention may have only short-term effects.

Despite these limitations, the study's results have practical implications. The structured palliative care intervention, administered by trained nurses, had positive effects on patients' quality of life and life satisfaction. These findings support the integration of nurse-led palliative care programs into oncology services in Iran. Additionally, the culturally tailored educational components could serve as a model for similar interventions in settings with similar cultural and healthcare structures.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that palliative care services improved patients' life satisfaction and all dimensions of quality of life (Except emotional functioning, sore throat, and diarrhea) in cancer patients. Therefore, nurses can play a crucial role in clinical settings by providing education and palliative care to manage symptoms and side effects of treatment, thereby enhancing patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. It is recommended that future studies develop targeted interventions to improve aspects of emotional well-being and specific physical symptoms. Additionally, long-term follow-up studies are necessary to assess the sustainability of the benefits of palliative care. Moreover, examining the impact of palliative care on families and caregivers, as well as its cost-effectiveness, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of its value.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a PhD dissertation in nursing from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to those who supported this work. Additionally, we extend our special gratitude to the patients who kindly participated in the study.

Funding sources

None.

Ethical statement

All ethical considerations in human studies have been strictly upheld, including the protection of confidentiality, obtaining informed consent, the participants' right to withdraw from the study at any time, and compliance with ethical publication practices. Patients were provided with detailed information regarding the purpose and procedures of the study, and the principles of research ethics were followed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring that all ethical guidelines were actively implemented throughout the study. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, under the Ethics Code: IR.SBMU.CRC.REC.1400.018.

Conflicts of interest

The authors state that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

M.K. and M.R. contributed to the formation of the research idea. M.K., M.R., and ME.A. participated in the study design. M.K. conducted the sampling. M.K. and K.N. performed the data analysis and interpretation. Sh.S.A prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Sh.S.A and H.E. reviewed and completed the manuscript. All authors participated sufficiently and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data will be accessible upon reasonable request, pending review by the research team and consideration of data confidentiality.

Full-Text: (474 Views)

Introduction

Cancer is one of the most critical health problems worldwide (1). Statistics show that the number of people affected by cancer will reach 21 million by 2030 (2). In Iran, cancer is also the third leading cause of death (3).

Receiving a cancer diagnosis significantly stresses both the patient and their family. The physical symptoms, psychological distress, social needs, and spiritual suffering profoundly disrupt their lives (4). Additionally, cancer treatments often result in side effects and, in some instances, permanent disorders, disabilities, and a reduced quality of life (5). Quality of life is a complex, multidimensional concept associated with indicators such as life satisfaction, physical health, social well-being, hopefulness, and mental health (6). In patients with cancer, the primary goal of nursing care is to enhance individual functioning and maximize quality of life (7). One way to achieve this goal is through the provision of palliative care (8).

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary field that focuses on enhancing the quality of life for patients with life-threatening illnesses, as well as supporting their families and caregivers. It addresses symptoms related to the disease, meets communication and decision-making needs, and relieves discomfort caused by the illness (9). Palliative care is founded on the belief that, in the final stages of disease, patients require greater support for compassionate human care than invasive interventions, while still benefiting from both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to symptom management (10). This care is delivered to alleviate symptoms, reduce the side effects of treatment, and improving the quality of life in individuals suffering from life-threatening illnesses such as cancer (11). Palliative care can minimize unplanned hospitalizations and the economic burden associated with cancer (12). It leads to improved symptom control, pain management, and reduced anxiety for both patients and their families, while ensuring high-quality care (13). A systematic review of 43 randomized controlled trials (N = 12,731) found that palliative care interventions can significantly improve patients’ quality of life, alleviate symptoms, and lead to higher patient and caregiver satisfaction (14).

In the coming years, there will be an increase in the number of patients with chronic illnesses, making their care one of the significant challenges for the healthcare system (15). Despite the growing need for palliative care, its implementation in Iran faces substantial challenges, including inadequate organizational support, limited specialized training, a lack of national guidelines, and cultural barriers (16). Currently, 37% of countries worldwide have implemented national operational policies for palliative care. This is despite the fact that 80% of individuals in need of palliative care live in low-income countries, where such services are scarce (17). Iran is among the nations where palliative care has not been comprehensively integrated into the health system. As the burden of chronic illnesses such as cancer continues to rise, integrating palliative care into routine health services has become a strategic priority to improve patient outcomes (18).

Despite the extensive evidence supporting the effectiveness of palliative care, context-specific and culturally sensitive interventions are scarce. This study aimed to facilitate the implementation of a palliative care program that includes education, psychological support, symptom management, individual and family counseling, and the enhancement of coping skills, to improve patients’ quality of life and life satisfaction within the cultural context of Iran.

Methods

This quasi-experimental study involved 320 patients with breast, tongue, stomach, thyroid, osteosarcoma, and colon cancer who were referred to Shohadaye Tajrish Teaching Hospital, a university hospital in Tehran, Iran, between May and October 2024. Patients were selected using convenience sampling. The sample size was determined based on similar previous studies on palliative care interventions in cancer patients, considering an expected moderate effect size, a power of 80%, and a significance level of 0.05, while accounting for potential attrition (19).

Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study, being at least 18 years old, literacy (The ability to read and write), the ability to understand and speak Persian, having been diagnosed with cancer at least six months before the study, and being aware of the diagnosis. Exclusion criteria included individuals with psychological conditions that significantly impaired their daily functioning or ability to participate in the study, a history of psychiatric hospitalization, or unsupervised use of psychotropic medications.

To develop the palliative care content, related service packages were utilized in the form of a translated version of the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care (20), under the technical supervision of the Office for Health Promotion and Nursing Services, affiliated with the Deputy for Nursing. This package was implemented by nurses who had received specialized training in palliative care. Since the care program should be tailored to the patients’ level of understanding, the researcher attempted to avoid using medical terminology that was difficult for the patients to comprehend. Several medical and nursing professors reviewed the content validity of the educational materials. After incorporating their suggestions and comments, the materials were ready for use. Additionally, to assess the face validity of the texts in terms of simplicity and patient understanding, 10 participants were asked to review the texts and confirm their validity in the above aspects.

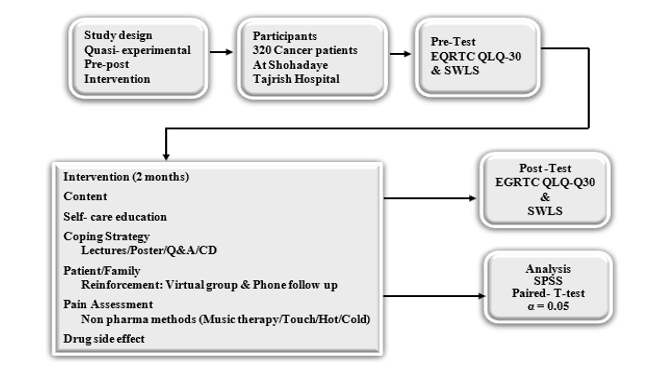

This program included various educational components designed to enhance patient self-care, identify barriers to information access for patients and caregivers, improve coping skills in stressful situations, and assess pain. This was achieved using appropriate tools, such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), as well as non-pharmacological methods, including music therapy, therapeutic touch, hot and cold therapy for pain management, and education about the side effects of drugs. Initially, the patients completed the questionnaires as a pre-test. Palliative care services were provided over six sessions, each lasting two hours, and conducted over a period of two months. These sessions included interactive lectures, discussions, and Q&A sessions, held in groups in the hospital classroom. Visual aids such as computer graphics and posters were also used to facilitate learning. At the end of each session, booklets, pamphlets, and CDs containing the key educational points were distributed to patients and their companions to help them retain and apply the information. Additionally, educational content was reinforced through social media channels where patients were added for ongoing engagement. To support the implementation of palliative care, researchers followed up with patients via telephone to address their questions and concerns. Following the palliative care intervention, patients followed the structured program for eight weeks. The structured follow-up program consisted of three biweekly telephone calls conducted by 15 shift nurses who had received specialized training.

During these calls, the patients’ overall condition, adherence to the recommendations provided during the palliative care sessions, potential challenges in symptom management, and emotional or supportive needs were assessed. If necessary, patients were guided to receive additional services or referred to relevant specialists for further care. The follow-up program aimed to sustain and enhance the intervention's effects while offering continuous support to patients after the in-person sessions ended. Ultimately, the post-test questionnaires were completed. The intervention flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

Cancer is one of the most critical health problems worldwide (1). Statistics show that the number of people affected by cancer will reach 21 million by 2030 (2). In Iran, cancer is also the third leading cause of death (3).

Receiving a cancer diagnosis significantly stresses both the patient and their family. The physical symptoms, psychological distress, social needs, and spiritual suffering profoundly disrupt their lives (4). Additionally, cancer treatments often result in side effects and, in some instances, permanent disorders, disabilities, and a reduced quality of life (5). Quality of life is a complex, multidimensional concept associated with indicators such as life satisfaction, physical health, social well-being, hopefulness, and mental health (6). In patients with cancer, the primary goal of nursing care is to enhance individual functioning and maximize quality of life (7). One way to achieve this goal is through the provision of palliative care (8).

Palliative care is an interdisciplinary field that focuses on enhancing the quality of life for patients with life-threatening illnesses, as well as supporting their families and caregivers. It addresses symptoms related to the disease, meets communication and decision-making needs, and relieves discomfort caused by the illness (9). Palliative care is founded on the belief that, in the final stages of disease, patients require greater support for compassionate human care than invasive interventions, while still benefiting from both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches to symptom management (10). This care is delivered to alleviate symptoms, reduce the side effects of treatment, and improving the quality of life in individuals suffering from life-threatening illnesses such as cancer (11). Palliative care can minimize unplanned hospitalizations and the economic burden associated with cancer (12). It leads to improved symptom control, pain management, and reduced anxiety for both patients and their families, while ensuring high-quality care (13). A systematic review of 43 randomized controlled trials (N = 12,731) found that palliative care interventions can significantly improve patients’ quality of life, alleviate symptoms, and lead to higher patient and caregiver satisfaction (14).

In the coming years, there will be an increase in the number of patients with chronic illnesses, making their care one of the significant challenges for the healthcare system (15). Despite the growing need for palliative care, its implementation in Iran faces substantial challenges, including inadequate organizational support, limited specialized training, a lack of national guidelines, and cultural barriers (16). Currently, 37% of countries worldwide have implemented national operational policies for palliative care. This is despite the fact that 80% of individuals in need of palliative care live in low-income countries, where such services are scarce (17). Iran is among the nations where palliative care has not been comprehensively integrated into the health system. As the burden of chronic illnesses such as cancer continues to rise, integrating palliative care into routine health services has become a strategic priority to improve patient outcomes (18).

Despite the extensive evidence supporting the effectiveness of palliative care, context-specific and culturally sensitive interventions are scarce. This study aimed to facilitate the implementation of a palliative care program that includes education, psychological support, symptom management, individual and family counseling, and the enhancement of coping skills, to improve patients’ quality of life and life satisfaction within the cultural context of Iran.

Methods

This quasi-experimental study involved 320 patients with breast, tongue, stomach, thyroid, osteosarcoma, and colon cancer who were referred to Shohadaye Tajrish Teaching Hospital, a university hospital in Tehran, Iran, between May and October 2024. Patients were selected using convenience sampling. The sample size was determined based on similar previous studies on palliative care interventions in cancer patients, considering an expected moderate effect size, a power of 80%, and a significance level of 0.05, while accounting for potential attrition (19).

Inclusion criteria included willingness to participate in the study, being at least 18 years old, literacy (The ability to read and write), the ability to understand and speak Persian, having been diagnosed with cancer at least six months before the study, and being aware of the diagnosis. Exclusion criteria included individuals with psychological conditions that significantly impaired their daily functioning or ability to participate in the study, a history of psychiatric hospitalization, or unsupervised use of psychotropic medications.

To develop the palliative care content, related service packages were utilized in the form of a translated version of the Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care (20), under the technical supervision of the Office for Health Promotion and Nursing Services, affiliated with the Deputy for Nursing. This package was implemented by nurses who had received specialized training in palliative care. Since the care program should be tailored to the patients’ level of understanding, the researcher attempted to avoid using medical terminology that was difficult for the patients to comprehend. Several medical and nursing professors reviewed the content validity of the educational materials. After incorporating their suggestions and comments, the materials were ready for use. Additionally, to assess the face validity of the texts in terms of simplicity and patient understanding, 10 participants were asked to review the texts and confirm their validity in the above aspects.

This program included various educational components designed to enhance patient self-care, identify barriers to information access for patients and caregivers, improve coping skills in stressful situations, and assess pain. This was achieved using appropriate tools, such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), as well as non-pharmacological methods, including music therapy, therapeutic touch, hot and cold therapy for pain management, and education about the side effects of drugs. Initially, the patients completed the questionnaires as a pre-test. Palliative care services were provided over six sessions, each lasting two hours, and conducted over a period of two months. These sessions included interactive lectures, discussions, and Q&A sessions, held in groups in the hospital classroom. Visual aids such as computer graphics and posters were also used to facilitate learning. At the end of each session, booklets, pamphlets, and CDs containing the key educational points were distributed to patients and their companions to help them retain and apply the information. Additionally, educational content was reinforced through social media channels where patients were added for ongoing engagement. To support the implementation of palliative care, researchers followed up with patients via telephone to address their questions and concerns. Following the palliative care intervention, patients followed the structured program for eight weeks. The structured follow-up program consisted of three biweekly telephone calls conducted by 15 shift nurses who had received specialized training.

During these calls, the patients’ overall condition, adherence to the recommendations provided during the palliative care sessions, potential challenges in symptom management, and emotional or supportive needs were assessed. If necessary, patients were guided to receive additional services or referred to relevant specialists for further care. The follow-up program aimed to sustain and enhance the intervention's effects while offering continuous support to patients after the in-person sessions ended. Ultimately, the post-test questionnaires were completed. The intervention flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The intervention flowchart |

The data collection tool consisted of a three-part questionnaire. The first part gathered demographic information and disease-related variables, including age, gender, education level, marital status, and type of cancer. The second part of the assessment was the EORTC QLQ-C30 Quality of Life Questionnaire, specifically designed for cancer patients. This questionnaire consists of 30 items that measure quality of life across five functional domains: physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social. Additionally, it addresses nine symptom domains, which include fatigue, pain, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, and financial difficulties related to the illness. There is also one global quality of life domain included in the assessment (21). Scores for each domain ranged from 0 to 100. In the functional and international quality of life domains, a higher score indicates a better condition, while in the symptom domains, a higher score indicates greater symptom severity or discomfort. The EORTC QLQ-C30 has demonstrated good psychometric properties across diverse cancer populations. The internal consistency reliability, measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was greater than 0.70 for most functional and symptom scales. The tool also demonstrated strong content, construct, and criterion validity, making it suitable for evaluating quality of life in oncology settings (22,23). The third part was the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener et al. (1985) (24). This tool consists of five items rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly disagree" (Score 1) to "strongly agree" (Score 7). The scale has demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values typically exceeding 0.80, and strong test-retest reliability over time. Its validity has been confirmed through correlations with measures of subjective well-being, mental health, and emotional functioning (25,26). To establish face and content validity, 10 expert faculty members reviewed the tools, and their feedback was incorporated into the development process. For reliability assessment, questionnaires were administered to 20 patients with cancer. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated, resulting in 0.96 for the quality-of-life questionnaire and 0.97 for the satisfaction with life scale.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26, applying statistical tests including paired t-tests at a significance level of 0.05, along with descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The normality of the data distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Results

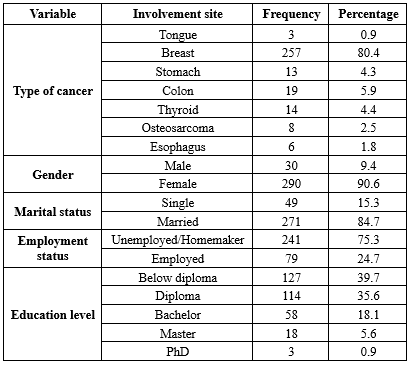

The results showed that the mean age of the participants was 50.67 years with a standard deviation of 13.23. The participants’ ages ranged from 36 to 71 years (36-71). Most of the participants had breast cancer. The mean duration of disease was 2.5 ± 1.2 years. Other demographic variables are presented descriptively in Table 1.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26, applying statistical tests including paired t-tests at a significance level of 0.05, along with descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. The normality of the data distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Results

The results showed that the mean age of the participants was 50.67 years with a standard deviation of 13.23. The participants’ ages ranged from 36 to 71 years (36-71). Most of the participants had breast cancer. The mean duration of disease was 2.5 ± 1.2 years. Other demographic variables are presented descriptively in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of cancer patients (n=320)

|

|

Table 2. Quality of life and satisfaction before and after palliative care (n=320)

* Paired t-test |

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of a palliative care intervention on the quality of life and satisfaction among patients with cancer. The results showed significant improvement in patients' quality of life, except for emotional functioning, sore throat, and diarrhea.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the quality of life in palliative care. Nevertheless, the topic has been examined from various viewpoints, and there is no thorough evaluation of the available evidence. Additionally, the role of health-related quality of life in terminal or permanently disabling illnesses, which are among the leading causes of distress and reduced quality of life, remains controversial. Patients are often referred to palliative care when curative treatment is no longer effective (27). In this regard, a study's findings showed that palliative care improves the quality of life for patients with severe, end-stage illnesses at the end of life. Palliative care services reduce patient symptoms and eliminate the need for unnecessary medical interventions and imaging, thereby enhancing the quality of life for patients and their families compared to non-palliative care units (28). A study conducted in Indonesia demonstrated that the intervention resulted in significant improvements in emotional and social functioning, as well as alleviations in pain, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, and financial difficulties among patients (29). The findings of a meta-review by Demuro et al. (2024), which examined 14 systematic reviews, confirmed the effectiveness of palliative care interventions for patients with end-stage conditions or permanent disabilities (27). These findings align with previous evidence supporting the benefits of nurse-led palliative care programs in enhancing the physical, psychological, and emotional well-being of patients with advanced illnesses (30,31).

The current study further enhances understanding by implementing a culturally adapted model within Iran's healthcare system, where palliative care remains in its developmental phase. In Iran, the delivery of palliative care faces several systemic challenges, including insufficient nurse training, lack of infrastructure, and cultural taboos surrounding death and end-of-life conversations (32,33). Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that structured, culturally sensitive care provided by trained nurses under professional supervision can lead to significant improvements in patient outcomes. This suggests a practical pathway for expanding palliative services, even in resource-constrained hospital settings.

Findings regarding life satisfaction suggest that palliative care services have a positive impact on the life satisfaction of cancer patients. Measuring patient satisfaction with the services provided by the care team is crucial for evaluating the quality-of-care outcomes. This measurement offers valuable insights into patients’ experiences with these services, assesses their treatment adherence, identifies structural weaknesses, and evaluates the performance of the care team (34). A study conducted in Egypt, which assessed elderly patients’ satisfaction with palliative care services for cancer, revealed that 42% of patients were indifferent to the quality of palliative care, and 47% expressed moderate satisfaction with healthcare providers. These findings differ from those of the present study (35). This discrepancy may be attributed to cultural differences, the study population, and the training and experience of the palliative care team. In another study conducted in Bangladesh, which evaluated patient satisfaction with palliative care, over 88% of patients were satisfied with the services provided by the care team. The leading indicators of satisfaction in this study included assessment of physical symptoms, information on pain management, inclusion of family members in decision-making, coordination of care among healthcare providers, and the availability of physicians (34).

Although patient satisfaction with healthcare services is a key indicator of care quality, it is worth noting that life satisfaction is a broader and more complex concept. Life satisfaction encompasses various domains, including physical health, psychological well-being, social support, spiritual fulfillment, and the individual’s sense of purpose. While the quality of care received can influence life satisfaction, it is only one of many contributing factors. Therefore, studies that focus exclusively on patient satisfaction with care services may not fully capture the multidimensional nature of life satisfaction. In this study, the observed improvements in life satisfaction may reflect the cumulative impact of symptom relief, emotional support, family engagement, and culturally relevant education provided through the structured palliative care intervention.

One limitation of the study was the potential impact of patients' knowledge, previous experiences, motivation, and interest on the outcomes. Additionally, individual differences and the mental and emotional states of the patients at the time of completing the questionnaire may have influenced the program's implementation. These factors were beyond the researchers' control. Furthermore, the study's generalizability was limited by its quasi-experimental design and the use of convenience sampling from a single hospital in Tehran. The findings may not apply to the broader population of cancer patients in Iran or other cultural contexts. Future research utilizing randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs and multi-center sampling could enhance the external validity of the results. Other limitations of the study include the duration of the intervention and the follow-up period. Various factors influence quality of life and life satisfaction, and the results from the educational intervention may have only short-term effects.

Despite these limitations, the study's results have practical implications. The structured palliative care intervention, administered by trained nurses, had positive effects on patients' quality of life and life satisfaction. These findings support the integration of nurse-led palliative care programs into oncology services in Iran. Additionally, the culturally tailored educational components could serve as a model for similar interventions in settings with similar cultural and healthcare structures.

Conclusion

The findings of this study showed that palliative care services improved patients' life satisfaction and all dimensions of quality of life (Except emotional functioning, sore throat, and diarrhea) in cancer patients. Therefore, nurses can play a crucial role in clinical settings by providing education and palliative care to manage symptoms and side effects of treatment, thereby enhancing patients’ quality of life and satisfaction. It is recommended that future studies develop targeted interventions to improve aspects of emotional well-being and specific physical symptoms. Additionally, long-term follow-up studies are necessary to assess the sustainability of the benefits of palliative care. Moreover, examining the impact of palliative care on families and caregivers, as well as its cost-effectiveness, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of its value.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a PhD dissertation in nursing from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to those who supported this work. Additionally, we extend our special gratitude to the patients who kindly participated in the study.

Funding sources

None.

Ethical statement

All ethical considerations in human studies have been strictly upheld, including the protection of confidentiality, obtaining informed consent, the participants' right to withdraw from the study at any time, and compliance with ethical publication practices. Patients were provided with detailed information regarding the purpose and procedures of the study, and the principles of research ethics were followed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring that all ethical guidelines were actively implemented throughout the study. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, under the Ethics Code: IR.SBMU.CRC.REC.1400.018.

Conflicts of interest

The authors state that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

M.K. and M.R. contributed to the formation of the research idea. M.K., M.R., and ME.A. participated in the study design. M.K. conducted the sampling. M.K. and K.N. performed the data analysis and interpretation. Sh.S.A prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Sh.S.A and H.E. reviewed and completed the manuscript. All authors participated sufficiently and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data will be accessible upon reasonable request, pending review by the research team and consideration of data confidentiality.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Nursing

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Zendehdel K. Cancer statistics in IR Iran in 2018. Basic & Clinical Cancer Research. 2019;11(1):1-4. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

3. Khashmi M, Tabarsy B, Aghahosseini S S. Correlation between Spiritual Health and Perceived Stress in Cancer Patients undergoing Chemotherapy. Knowledge of Nursing. 2024;1(4):301-10. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

4. Bubis LD, Davis L, Mahar A, Barbera L, Li Q, Moody L, et al. Symptom burden in the first year after cancer diagnosis: an analysis of patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(11):1103-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Cotogni P, Stragliotto S, Ossola M, Collo A, Riso S. The role of nutritional support for cancer patients in palliative care. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):306. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Maggino F. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research: Springer; 2023. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

7. Aghahosseini Sh. A comprehensive review on the diagnosis and the treatment of some type of cancer. Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing; 2024. [View at Publisher]

8. Karami M , Akbari M E, Abbaszadeh A, Shirinabadi Farahani A, Alavi Majd H, Rassouli M. Present Status of Obtaining Palliative Care to Cancer Patients: SWOT Analysis. Int J Cancer Manag. 2025; 18(1):e149900. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

9. Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, Lovell N, Evans CJ, Higginson IJ, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017;15(1)):102. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Hui D, Bruera E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020 20; 38(9): 852-65. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Naghi Beyranvand M, Mousavi SF. The effect of palliative care on the quality of life of cancer patients: a systematic review. Nursing Developement in Health. 2020; 11(1): 8-17. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

12. Hassankhani H, Dehghannezhad J, Rahmani A, Ghafourifard M, Valizadeh F. Improvement of a home palliative care program in cancer patients: An action research study. Journal of Hayat. 2023;28(4):388-404. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

13. Shin JA, Parkes A, El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Knight H, Gallagher ER, et al. Retrospective evaluation of palliative care and hospice utilization in hospitalized patients with metastatic breast cancer. Palliat Med. 2016;30(9):854-61. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, Dionne-Odom JN, Ernecoff NC, Hanmer J, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104-14. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. World Health Organization. World health statistics 2025: Monitoring health for the SDGs. Geneva: WHO; 2025. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

16. Amroud MS, Raeissi P, Hashemi SM, Reisi N, Ahmadi SA. Investigating the challenges and barriers of palliative care delivery in Iran and the World: A systematic review study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;30;10:246. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

17. Sharkey L, Loring B, Cowan M, Riley L, Krakauer EL. National palliative care capacities around the world: results from the world health organization noncommunicable disease country capacity survey. Palliat Med. 2018; 32(1): 106-13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. World Health Organization. Palliative care: key facts. Geneva: WHO; 2024 . [View at Publisher]

19. Orun OM, Shinall Jr MC, Hoskins A, Morgan E, Karlekar M, Martin SF,et al. Statistical analysis plan for the Surgery for Cancer with Option of Palliative Care Expert (SCOPE) trial: a randomized controlled trial of a specialist palliative care intervention for patients undergoing surgery for cancer. Trials. 2021;22(1):314. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Cherny NI, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, Currow DC, editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2021 [View at Publisher] [DOI]

21. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-76. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. Motamed N, Ayatollahi AR, Zare N, Sadeghi Hassanabadi A. Validity and reliability of the Persian translation of the SF-36 version 2 questionnaire. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(3):349-57. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Safaee A, Moghim Dehkordi B. Validation study of a quality of life (QOL) questionnaire for use in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8(4):543-46. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71-5. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. Maroufizadeh S, Ghaheri A, Samani RO, Ezabadi Z. Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in Iranian infertile women. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14(1):57-62. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Nooripour R, Hosseinian S, Ghanbari N, Haghighat S, Matacotta JJ, Gasparri ML. Validation of the Persian version of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) in Iranian women with breast Cancer. Current Psychology. 2023;42:2993–3000. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

27. Demuro M, Bratzu E, Lorrai S, Preti A. Quality of Life in Palliative Care: A Systematic Meta-Review of Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2024;20(1):e17450179183857. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Darrudi A, Poupak AH, Darroudi R, Sargazi N, Zendehdel K, Sallnow L, et al. Financial cost of end-of-life cancer care in palliative care units (PCUs) and non-PCUs in Iran: insights from low-and middle-income countries. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2024;18:26323524241299819. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

29. Kristanti MS, Setiyarini S, Effendy C. Enhancing the quality of life for palliative care cancer patients in Indonesia through family caregivers: a pilot study of basic skills training. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):4. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Biswas J, Faruque M, Banik PC, Ahmad N, Mashreky SR. Satisfaction with care provided by home‐based palliative care service to the cancer patients in Dhaka City of Bangladesh: A cross‐sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2022;5(6):e908. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

31. Kamel AKM, El-Guindy HA, Mohamed AAE, Saleh ASEM. Assessment of Elderly Patient Satisfaction about Palliative Care Services for Cancer. NILES journal for Geriatric and Gerontology. 2023;6(1):114-32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

32. Rassouli M, Sajjadi M. Palliative care in Iran: Moving toward the development of palliative care for cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(3):240-4. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Khanali Mojen L. Palliative Care in Iran: The Past, the Present and the Future. Support Palliat Care Cancer. 2017;1(1):8-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

34. Kolagari S, Khoddam H, Guirimand F, Taymouri Yeganeh L, Mahmoudian A. Psychometric properties of the ‘patients’ perspective of the quality of palliative care scale.’ Indian J Palliat Care. 2022;28(1):64–74. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

35. Mahmoud Kamel A, El-Guindy HA, Mohamed AAE, Saleh ASE. Assessment of elderly patient satisfaction about palliative care services for cancer. Niles Nursing Journal. 2023;6(1):114–32. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |