Volume 22, Issue 4 (12-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(4): 28-33 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khanom H, Hossain S, Islam R, Baroi L, Rima R E A, Mitu J F, et al . Fear of childbirth and its associated factors among pregnant women in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (4) :28-33

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2076-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2076-en.html

Habiba Khanom1

, Sharmin Hossain2

, Sharmin Hossain2

, Rabiul Islam3

, Rabiul Islam3

, Liton Baroi4

, Liton Baroi4

, Eashmin Akter Rima R5

, Eashmin Akter Rima R5

, Jannatul Ferdoues Mitu6

, Jannatul Ferdoues Mitu6

, Chandra Das7

, Chandra Das7

, Sumaia Afroz8

, Sumaia Afroz8

, Jannatul Ferdowsy9

, Jannatul Ferdowsy9

, Aysha Sultana Luvna10

, Aysha Sultana Luvna10

, Lita Bose11

, Lita Bose11

, Shukla Sarker12

, Shukla Sarker12

, Alamgir Hossain13

, Alamgir Hossain13

, Sharmin Hossain2

, Sharmin Hossain2

, Rabiul Islam3

, Rabiul Islam3

, Liton Baroi4

, Liton Baroi4

, Eashmin Akter Rima R5

, Eashmin Akter Rima R5

, Jannatul Ferdoues Mitu6

, Jannatul Ferdoues Mitu6

, Chandra Das7

, Chandra Das7

, Sumaia Afroz8

, Sumaia Afroz8

, Jannatul Ferdowsy9

, Jannatul Ferdowsy9

, Aysha Sultana Luvna10

, Aysha Sultana Luvna10

, Lita Bose11

, Lita Bose11

, Shukla Sarker12

, Shukla Sarker12

, Alamgir Hossain13

, Alamgir Hossain13

1- Department of Nursing Management, Kumudini Nursing College, Mirzapur, Tangail, Bangladesh , orpitakhanom.sumona77@gmail.com

2- Department of Health Promotion and Health Education, Bangladesh University of Health Sciences, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3- Division of Public Health, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, United States of America; Department of Public Health, Independent University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4- DNCC Covid-19 Dedicated Hospital, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh

5- Upazila Health Complex Zanjira, Shariatpur, Bangladesh

6- BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health (JPGSPH), Midwifery Education Program, BRAC JPGSPH, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

7- Gopalganj Rasel Nursing College, Muksudpur, Gopalganj, Dhaka, Bangladesh

8- National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases (NICVD), Dhaka, Bangladesh

9- Prince Nursing College, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh

10- Army Nursing College, Cumilla, Bangladesh

11- Department of Epidemiology, Prince Nursing College, Savar, Bangladesh

12- Nabojug College, Dhamrai, Dhaka, Bangladesh

13- Bangladesh Critical Care and General Hospital, Lalmatia, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2- Department of Health Promotion and Health Education, Bangladesh University of Health Sciences, Dhaka, Bangladesh

3- Division of Public Health, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, United States of America; Department of Public Health, Independent University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4- DNCC Covid-19 Dedicated Hospital, Mohakhali, Dhaka, Bangladesh

5- Upazila Health Complex Zanjira, Shariatpur, Bangladesh

6- BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health (JPGSPH), Midwifery Education Program, BRAC JPGSPH, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

7- Gopalganj Rasel Nursing College, Muksudpur, Gopalganj, Dhaka, Bangladesh

8- National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases (NICVD), Dhaka, Bangladesh

9- Prince Nursing College, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh

10- Army Nursing College, Cumilla, Bangladesh

11- Department of Epidemiology, Prince Nursing College, Savar, Bangladesh

12- Nabojug College, Dhamrai, Dhaka, Bangladesh

13- Bangladesh Critical Care and General Hospital, Lalmatia, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Full-Text [PDF 502 kb]

(215 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (953 Views)

A total of 65.6% had not attended childbirth preparation classes. Nearly half (48.9%) were in their second pregnancy, and 30.5% reported having had one miscarriage. The majority (55.7%) preferred normal vaginal delivery, while 44.3% preferred cesarean section, mainly due to fear of complications (Table 2).

Factors contributing to fear of childbirth

Assessment of childbirth-related fears identified five domains. In relation to factor 1 (Physical process of childbirth), the highest anxiety was reported regarding pain and complications, including uterine contractions (51.1%), episiotomy (55.0%), ruptures (48.1%), prolonged labor (48.5%), panic (43.9%), and difficulty breathing or pushing (41.6%). For factor 2 (Mother and child well-being), concerns centered on safety outcomes such as stillbirth (52.3%), birth injuries (49.6%), pregnancy complications (46.9%), and other adverse events (48.5%). Factor 3 (Healthcare personnel) captured fears related to communication and vulnerability, including asking “silly” questions (58.0%), exclusion from decision-making (32.8%), unfriendly staff (27.1%), and being left alone (29.0%). Factor 4 (Family life) involved fears of sexual difficulties (44.7%), relationship strain (32.4%), and childcare challenges (32.4%). Factor 5 (Cesarean section) reflected apprehension regarding surgical delivery (41.2%, Tables 3 and 4).

Higher FOC was significantly associated with younger maternal age (18-23 years; 30.8%) (p < 0.001), early marriage (28.6%) (p < 0.001), lower maternal education (40.0%) (p < 0.001), housewife status (29.4%) (p < 0.001), and husbands’ lower education (90.9%) or government employment (32.4%) (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). Rural residence (4.0%) (p < 0.001), primary support from spouse (18.1%) (p < 0.001), and lower family income were also linked to higher FOC (p < 0.001). These findings indicate that younger age, lower education, limited spousal support, and lower socioeconomic status are key predictors of heightened fear of childbirth.

Ordinal regression and multivariate logistic regression

Ordinal regression showed that younger maternal age (< 25 years) (AOR = 1.86; 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.03; p = 0.014), lower maternal education (AOR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.02 - 2.49; p = 0.041), husbands’ lower education (AOR = 1.71; 95% CI: 1.02 - 2.87; p = 0.043), lack of spousal support (AOR = 1.97; 95% CI: 1.19 - 3.26; p = 0.008), and non-attendance in childbirth preparation classes (AOR = 1.75; 95% CI: 1.08 - 2.84; p = 0.023) were significant predictors of higher FOC (Table 6).

In the multivariate logistic regression model, younger age (<25 years) (AOR = 2.47; 95% CI: 1.34 - 4.56; p = 0.004), lower maternal education (AOR = 2.05; 95% CI: 1.12 - 3.77; p = 0.021), husbands’ lower education (AOR = 2.28; 95% CI: 1.19 - 4.39; p = 0.012), housewife status (AOR = 1.91; 95% CI: 1.03 - 3.53; p = 0.038), rural residence (AOR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.66; p = 0.017), limited spousal support (AOR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.38 - 5.06; p = 0.003), low income (≤25,000 BDT/month) (AOR = 1.95; 95% CI: 1.08 - 3.51; p = 0.026), and non-attendance in childbirth classes (AOR = 2.33; 95% CI: 1.21 - 4.49; p = 0.011) remained significant (Table 6).

Overall, younger age, low education, limited partner support, low income, and lack of prenatal class attendance were the strongest predictors of high FOC. The models demonstrated good fit (Ordinal regression: Nagelkerke R² = 0.38, χ² (8) = 76.21, p < 0.001; Logistic regression: Nagelkerke R² = 0.47, χ² (8) = 89.64, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the main domains of fear of childbirth (FOC) among pregnant women and to examine the socio-demographic and obstetric factors associated with heightened fear. Our findings revealed that FOC is multifaceted, with the highest fear related to the physical process of childbirth, followed by concerns for maternal and neonatal well-being, healthcare personnel, family life, and cesarean section. Higher FOC was associated with younger age, lower education, limited spousal support, and lower socioeconomic status.

These results are consistent with a growing body of international research. In this study (6), which was a scoping review of Asian women, it was found that FOC is strongly influenced by cultural beliefs, lack of childbirth knowledge, and insufficient support, with younger and less educated women being particularly vulnerable. Their review included diverse Asian populations, highlighting the importance of context-specific interventions. Similarly, study (18) emphasized that FOC is shaped by personal beliefs, previous experiences, and perceived support, and can negatively impact maternal mental health and birth outcomes.

The relationship between childbirth beliefs and FOC was further explored by (8) in a Turkish sample, who found that negative beliefs about childbirth significantly increased fear, especially among women with limited education and support. The study (19) also reported that Turkish pregnant women with lower socioeconomic status and less access to healthcare resources experienced higher FOC, reinforcing the importance of addressing social determinants.

The prevalence and predictors of FOC have also been studied in China. The study (12) validated the Chinese version of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire and found that FOC was higher among women with less education and support. Similar study (20) used hierarchical regression analysis and identified similar predictors, including lower education, lack of information, and limited support.

Our results are further supported by systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This study (21) found that Turkish women with lower socioeconomic status and less access to healthcare resources had higher FOC. The similar study (9) reported similar findings in East African women, with younger age, lower education, and limited support being significant predictors. The study (22) studied Chinese women in late pregnancy and found that FOC was associated with lower education, lack of childbirth knowledge, and insufficient support.

Our findings regarding the protective effect of childbirth education are supported by (10), who studied Iranian primiparous women and found that regular attendance at childbirth preparation classes reduced FOC, anxiety, and depression. Their participants were grouped by class attendance, and those regularly attending reported the lowest fear and anxiety. The similar study (3) conducted a longitudinal cohort study in Sweden and found that FOC fluctuates during pregnancy and is influenced by perceived support from healthcare providers, with women reporting higher support experiencing less fear.

The study (5) examined Iranian primigravid women and found that lower education, lower income, and lack of support were associated with higher FOC, which aligns with our findings. The similar study (11) conducted qualitative research among urban Indian women and highlighted the role of social and familial expectations, as well as the impact of negative birth stories, in shaping FOC. The study (23) found that both pregnant women and their partners in Turkey experienced FOC, with communication and support from healthcare staff being key factors.

The impact of FOC on delivery preferences is also well documented. The study (16) found that higher FOC was associated with a preference for elective cesarean section among Egyptian women. This study (15) analyzed Bangladeshi data and reported that FOC and related factors contributed to higher rates of cesarean delivery. Our study similarly found that women with higher FOC were more likely to prefer cesarean section, often due to concerns about pain and complications.

A key limitation of our study is the reliance on self-reported measures, which may introduce response bias and affect the accuracy of the findings. This limitation is common in FOC research, as noted by (18) and others. Another limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of pregnant women in Bangladesh. Future studies should consider simple random sampling. Despite this, a major strength of our study is the diverse sample and systematic identification of FOC domains, which provides a nuanced understanding of the issue and supports the development of targeted, culturally appropriate interventions.

In summary, our study confirms that FOC is a complex phenomenon influenced by demographic, educational, psychosocial, and cultural factors. The findings are consistent with recent international research and highlight the need for comprehensive, multi-level strategies-including education, psychological support, and partner involvement-to reduce FOC and improve maternal well-being.

Conclusion

This study identified that fear of childbirth (FOC) among pregnant women is a multifaceted issue, with the greatest concerns centered on the physical process of childbirth, maternal and neonatal well-being, interactions with healthcare personnel, family life, and cesarean section. Our findings highlight that younger age, lower educational attainment, limited spousal support, and lower socioeconomic status are significant predictors of heightened FOC. Importantly, limited participation in childbirth preparation classes was observed among the majority of participants, and this lack of educational engagement may contribute to increased fear and anxiety surrounding childbirth. These results underscore the need for targeted interventions, such as expanding access to childbirth education and strengthening support systems, particularly for vulnerable groups. Addressing these factors through comprehensive, culturally sensitive strategies can help reduce FOC and promote better maternal mental health and birth outcomes. Future research should further explore effective approaches to increase participation in childbirth preparation and evaluate their impact on reducing FOC.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the pregnant women who participated in this study for their time and valuable insights. Special thanks are extended to the staff and management of Shariatpur Government Upazila Health Complex for their support and cooperation during data collection. We also acknowledge the contributions of our research assistants and data collectors, whose dedication made this study possible.

Funding sources

This study was self-funded, and no external funding was received.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Enam Medical College, Bangladesh (Memo No. EMC/IERB/2024/01-2). All participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained prior to their participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the research process.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there was no competing interest.

Author contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by HK, SH, ASL, JF, and RI. Data collection was carried out by SS, EAR, JFM, LB, ASL, and AH. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by LB, HK, JFM, ASL, and RI. The manuscript was drafted by HK, CD, JFM, JF, LB, and SA. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was undertaken by HK, SH, JFM, JF, ASL, and LB. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the study.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Full-Text: (31 Views)

Introduction

Fear of childbirth (FOC), a prevalent obstetric issue, negatively impacts women's health and is associated with factors such as higher socioeconomic status, depression, advanced maternal age, and prior operative births (1). Fear of childbirth (FOC) is a significant psychological concern that can profoundly affect the well-being of pregnant women and influence maternal and neonatal outcomes. Globally, FOC is recognized as a common experience, with a systematic review and meta-analysis (2) estimating the prevalence of tocophobia at approximately 14%, although rates vary widely across different populations and cultural contexts. Studies from Sweden and Iran, for example, have reported prevalence rates ranging from 19% to over 80%, depending on the population studied and the measurement tools used (3-5). The study by Hildingsson et al. (2017) showed that the prevalence of fear of birth was 22% in mid-pregnancy and 19% in late pregnancy (3). Another study by Mortazavi et al. (2018) revealed that 19.6% and 6.1% experienced moderate (Mean W-DEQ score ≥ 85) and severe (Mean W-DEQ score ≥ 100) fear of childbirth, respectively (4).

FOC is a multifaceted phenomenon influenced by a range of demographic, psychosocial, and cultural factors. Research has consistently shown that younger maternal age, lower educational attainment, limited social and spousal support, low socioeconomic status, and negative beliefs about childbirth are significant predictors of heightened FOC (6-9). Additionally, previous negative birth experiences, lack of childbirth preparation, and insufficient information about the birth process further contribute to increased fear (10-12).

In Bangladesh, maternal health remains a public health priority, with ongoing efforts to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. However, the psychological aspects of pregnancy, including FOC, have received comparatively less attention. Existing studies in Bangladesh have highlighted the prevalence of antenatal depression and anxiety, often linked to social determinants such as poverty, limited education, and lack of support (13,14). Furthermore, FOC has been associated with a preference for elective cesarean section, which is a growing trend in Bangladesh and may have implications for maternal and neonatal health outcomes (15).

Despite the global and regional significance of FOC, there is a paucity of research specifically examining its prevalence and associated factors among pregnant women in Bangladesh. Understanding the level of FOC and its determinants in this context is essential for developing targeted interventions to support maternal mental health and promote positive birth experiences. Therefore, this study determined the FOC level and its associated factors among pregnant women in Bangladesh, which informs policymakers to take interventions to improve maternal confidence and reduce fear during childbirth.

Methods

Study design and setting

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted between December 2023 and May 2024 at the Shariatpur Government Upazila Health Complex, Bangladesh, which provides antenatal, emergency, and specialist maternal care services.

Study participants and eligibility criteria

The study population consisted of pregnant women attending routine antenatal care at the facility during the study period. Both primiparous and multiparous women were eligible.

Inclusion criteria

In this study, a wide gestational range (18 - 37 weeks and above) with singleton pregnancies was included to capture a representative sample of women at different pregnancy stages. Participants who provided written informed consent were enrolled.

Exclusion criteria

Women with multiple pregnancies (e.g., twins), non-cephalic presentations, severe obstetric complications, or a documented history of physical or psychiatric illness (e.g., epilepsy, schizophrenia, severe depression) that might impair their ability to participate were excluded.

Sample size and sampling

The sample size was determined using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 program based on a multiple logistic regression model, as the study aimed to identify factors associated with different levels of FOC. Following Cohen’s (1988) recommendations for behavioral and health research, a medium effect size (Odds ratio ≈ 1.5; f² = 0.15), a significance level (α) of 0.05, and a statistical power (1–β) of 0.80 were applied. Considering up to 9 predictor variables (Socio-demographic) in the final model, the required minimum sample size was calculated as 238 participants.

This estimate is also consistent with the prevalence of FOC (80.8%) reported in Beiranvand et al. (2017) among Iranian primigravid women, ensuring comparability with prior studies in similar contexts (5). To account for a potential 10% non-response rate, the final target sample size was increased to 262 participants.

A convenience sampling technique was adopted, as the Shariatpur Government Upazila Health Complex functions as the main antenatal care center for the district, providing access to a broad cross-section of pregnant women. Probability-based approaches, such as multistage cluster sampling, were considered but were not feasible due to time and resource constraints (5).

Data collection instruments

Data were collected through structured face-to-face interviews using two validated tools: a Structured Interview Questionnaire adapted from (16) and the Melender (2002) Questionnaire.

1. Part I: Socio-demographic characteristics (9 items: age, education, religion, occupation, husband’s education, husband’s occupation, residence, income, etc.).

2. Part II: Obstetric history (8 items: parity, miscarriage history, gestational age, etc.) and birth mode preference with reasons.

3. Part III: Melender (2002) Questionnaire for assessing factors associated with FOC, consisting of five domains of fear: (A) childbirth process, (B) maternal and child well-being, (C) healthcare staff, (D) family life, and (E) cesarean section.

Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = agree, 2 = agree to some extent, 3 = disagree to some extent, 4 = do not agree) (17). Total scores ranged from 21 - 84, with higher scores indicating lower levels of fear. Fear levels were categorized into four ranges based on total scores: high (21 - 42), moderate (43 - 56), low (57 - 70), and no/minimal fear (71 - 84). Higher scores reflect reduced fear.

Validity and reliability of the instrument

The Melender questionnaire has demonstrated strong content and construct validity in multiple populations (16,17). Content validity was established through expert evaluation of items covering psychological, physical, and social dimensions of childbirth fear. Construct validity was confirmed through factor analysis in the original Finnish and subsequent cross-cultural adaptations, supporting the five-domain structure.

For internal consistency, the original study by Melender (2002) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87, indicating high reliability (17). Similarly, Abd El-Aziz et al. (2017) found a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 among Egyptian women, confirming cross-cultural reliability (16). In the present study, the adapted Bangla version of the tool showed satisfactory internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85, indicating acceptable reliability for use in the Bangladeshi context.

External validity was enhanced by adapting the questionnaire into both English and Bangla, ensuring linguistic and cultural appropriateness through back-translation and expert review by three maternal health specialists. A pretest with 20 pregnant women was conducted to assess clarity, comprehension, and cultural relevance; minor linguistic adjustments were made accordingly. Thus, the Melender (2002) Questionnaire demonstrated good psychometric robustness and suitability for assessing the multidimensional aspects of FOC in the current population (17).

Data collection procedure

Eligible participants were approached during antenatal visits. After the study objectives were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Data were collected through structured face-to-face interviews using a standardized questionnaire in Bangla, conducted by trained female interviewers to ensure clarity and comfort.

Data analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics (Means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages) were used to summarize socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Bivariate associations between socio-demographic factors and levels of FOC were examined using the chi-square test, and non-parametric analyses were applied where appropriate.

Ordinal and multivariate logistic regression analyses were then performed to identify predictors of higher FOC and high versus low/moderate FOC, respectively. Variables entered into the models included maternal age, maternal education, husband’s education, occupation, place of residence, monthly family income, spousal support, and attendance in childbirth preparation classes. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the strength of associations.

Model fit was assessed using the chi-square goodness-of-fit test and Nagelkerke R² values. The ordinal regression model demonstrated good fit (χ² (8) = 76.21, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R² = 0.38), while the multivariate logistic regression model also showed satisfactory fit (χ² (8) = 89.64, p < 0.001; Hosmer-Lemeshow p = 0.47; Nagelkerke R² = 0.47). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 262 pregnant women participated in the study, yielding a 100% response rate, as all eligible women who were approached during the study period consented and completed the interviews.

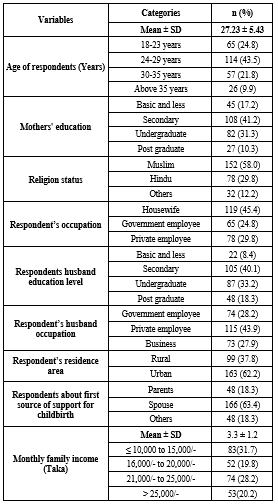

Socio-demographic characteristics

Most participants were aged 24 - 29 years (43.5%), had secondary education (41.2%), and were housewives (45.4%). About 62.2% lived in urban areas. Husbands predominantly worked in the private sector (43.9%), and 40.1% had secondary education. Most households reported monthly incomes of ≤ 25,000 BDT (Table 1).

Fear of childbirth (FOC), a prevalent obstetric issue, negatively impacts women's health and is associated with factors such as higher socioeconomic status, depression, advanced maternal age, and prior operative births (1). Fear of childbirth (FOC) is a significant psychological concern that can profoundly affect the well-being of pregnant women and influence maternal and neonatal outcomes. Globally, FOC is recognized as a common experience, with a systematic review and meta-analysis (2) estimating the prevalence of tocophobia at approximately 14%, although rates vary widely across different populations and cultural contexts. Studies from Sweden and Iran, for example, have reported prevalence rates ranging from 19% to over 80%, depending on the population studied and the measurement tools used (3-5). The study by Hildingsson et al. (2017) showed that the prevalence of fear of birth was 22% in mid-pregnancy and 19% in late pregnancy (3). Another study by Mortazavi et al. (2018) revealed that 19.6% and 6.1% experienced moderate (Mean W-DEQ score ≥ 85) and severe (Mean W-DEQ score ≥ 100) fear of childbirth, respectively (4).

FOC is a multifaceted phenomenon influenced by a range of demographic, psychosocial, and cultural factors. Research has consistently shown that younger maternal age, lower educational attainment, limited social and spousal support, low socioeconomic status, and negative beliefs about childbirth are significant predictors of heightened FOC (6-9). Additionally, previous negative birth experiences, lack of childbirth preparation, and insufficient information about the birth process further contribute to increased fear (10-12).

In Bangladesh, maternal health remains a public health priority, with ongoing efforts to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. However, the psychological aspects of pregnancy, including FOC, have received comparatively less attention. Existing studies in Bangladesh have highlighted the prevalence of antenatal depression and anxiety, often linked to social determinants such as poverty, limited education, and lack of support (13,14). Furthermore, FOC has been associated with a preference for elective cesarean section, which is a growing trend in Bangladesh and may have implications for maternal and neonatal health outcomes (15).

Despite the global and regional significance of FOC, there is a paucity of research specifically examining its prevalence and associated factors among pregnant women in Bangladesh. Understanding the level of FOC and its determinants in this context is essential for developing targeted interventions to support maternal mental health and promote positive birth experiences. Therefore, this study determined the FOC level and its associated factors among pregnant women in Bangladesh, which informs policymakers to take interventions to improve maternal confidence and reduce fear during childbirth.

Methods

Study design and setting

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted between December 2023 and May 2024 at the Shariatpur Government Upazila Health Complex, Bangladesh, which provides antenatal, emergency, and specialist maternal care services.

Study participants and eligibility criteria

The study population consisted of pregnant women attending routine antenatal care at the facility during the study period. Both primiparous and multiparous women were eligible.

Inclusion criteria

In this study, a wide gestational range (18 - 37 weeks and above) with singleton pregnancies was included to capture a representative sample of women at different pregnancy stages. Participants who provided written informed consent were enrolled.

Exclusion criteria

Women with multiple pregnancies (e.g., twins), non-cephalic presentations, severe obstetric complications, or a documented history of physical or psychiatric illness (e.g., epilepsy, schizophrenia, severe depression) that might impair their ability to participate were excluded.

Sample size and sampling

The sample size was determined using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 program based on a multiple logistic regression model, as the study aimed to identify factors associated with different levels of FOC. Following Cohen’s (1988) recommendations for behavioral and health research, a medium effect size (Odds ratio ≈ 1.5; f² = 0.15), a significance level (α) of 0.05, and a statistical power (1–β) of 0.80 were applied. Considering up to 9 predictor variables (Socio-demographic) in the final model, the required minimum sample size was calculated as 238 participants.

This estimate is also consistent with the prevalence of FOC (80.8%) reported in Beiranvand et al. (2017) among Iranian primigravid women, ensuring comparability with prior studies in similar contexts (5). To account for a potential 10% non-response rate, the final target sample size was increased to 262 participants.

A convenience sampling technique was adopted, as the Shariatpur Government Upazila Health Complex functions as the main antenatal care center for the district, providing access to a broad cross-section of pregnant women. Probability-based approaches, such as multistage cluster sampling, were considered but were not feasible due to time and resource constraints (5).

Data collection instruments

Data were collected through structured face-to-face interviews using two validated tools: a Structured Interview Questionnaire adapted from (16) and the Melender (2002) Questionnaire.

1. Part I: Socio-demographic characteristics (9 items: age, education, religion, occupation, husband’s education, husband’s occupation, residence, income, etc.).

2. Part II: Obstetric history (8 items: parity, miscarriage history, gestational age, etc.) and birth mode preference with reasons.

3. Part III: Melender (2002) Questionnaire for assessing factors associated with FOC, consisting of five domains of fear: (A) childbirth process, (B) maternal and child well-being, (C) healthcare staff, (D) family life, and (E) cesarean section.

Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = agree, 2 = agree to some extent, 3 = disagree to some extent, 4 = do not agree) (17). Total scores ranged from 21 - 84, with higher scores indicating lower levels of fear. Fear levels were categorized into four ranges based on total scores: high (21 - 42), moderate (43 - 56), low (57 - 70), and no/minimal fear (71 - 84). Higher scores reflect reduced fear.

Validity and reliability of the instrument

The Melender questionnaire has demonstrated strong content and construct validity in multiple populations (16,17). Content validity was established through expert evaluation of items covering psychological, physical, and social dimensions of childbirth fear. Construct validity was confirmed through factor analysis in the original Finnish and subsequent cross-cultural adaptations, supporting the five-domain structure.

For internal consistency, the original study by Melender (2002) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87, indicating high reliability (17). Similarly, Abd El-Aziz et al. (2017) found a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 among Egyptian women, confirming cross-cultural reliability (16). In the present study, the adapted Bangla version of the tool showed satisfactory internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85, indicating acceptable reliability for use in the Bangladeshi context.

External validity was enhanced by adapting the questionnaire into both English and Bangla, ensuring linguistic and cultural appropriateness through back-translation and expert review by three maternal health specialists. A pretest with 20 pregnant women was conducted to assess clarity, comprehension, and cultural relevance; minor linguistic adjustments were made accordingly. Thus, the Melender (2002) Questionnaire demonstrated good psychometric robustness and suitability for assessing the multidimensional aspects of FOC in the current population (17).

Data collection procedure

Eligible participants were approached during antenatal visits. After the study objectives were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Data were collected through structured face-to-face interviews using a standardized questionnaire in Bangla, conducted by trained female interviewers to ensure clarity and comfort.

Data analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics (Means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages) were used to summarize socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Bivariate associations between socio-demographic factors and levels of FOC were examined using the chi-square test, and non-parametric analyses were applied where appropriate.

Ordinal and multivariate logistic regression analyses were then performed to identify predictors of higher FOC and high versus low/moderate FOC, respectively. Variables entered into the models included maternal age, maternal education, husband’s education, occupation, place of residence, monthly family income, spousal support, and attendance in childbirth preparation classes. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the strength of associations.

Model fit was assessed using the chi-square goodness-of-fit test and Nagelkerke R² values. The ordinal regression model demonstrated good fit (χ² (8) = 76.21, p < 0.001; Nagelkerke R² = 0.38), while the multivariate logistic regression model also showed satisfactory fit (χ² (8) = 89.64, p < 0.001; Hosmer-Lemeshow p = 0.47; Nagelkerke R² = 0.47). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 262 pregnant women participated in the study, yielding a 100% response rate, as all eligible women who were approached during the study period consented and completed the interviews.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Most participants were aged 24 - 29 years (43.5%), had secondary education (41.2%), and were housewives (45.4%). About 62.2% lived in urban areas. Husbands predominantly worked in the private sector (43.9%), and 40.1% had secondary education. Most households reported monthly incomes of ≤ 25,000 BDT (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Distribution of socio-demographic characteristics of the pregnant women (N = 262)

n= Number of respondents; %= Percentage; M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; Others=Christian and Buddhist. |

A total of 65.6% had not attended childbirth preparation classes. Nearly half (48.9%) were in their second pregnancy, and 30.5% reported having had one miscarriage. The majority (55.7%) preferred normal vaginal delivery, while 44.3% preferred cesarean section, mainly due to fear of complications (Table 2).

Factors contributing to fear of childbirth

Assessment of childbirth-related fears identified five domains. In relation to factor 1 (Physical process of childbirth), the highest anxiety was reported regarding pain and complications, including uterine contractions (51.1%), episiotomy (55.0%), ruptures (48.1%), prolonged labor (48.5%), panic (43.9%), and difficulty breathing or pushing (41.6%). For factor 2 (Mother and child well-being), concerns centered on safety outcomes such as stillbirth (52.3%), birth injuries (49.6%), pregnancy complications (46.9%), and other adverse events (48.5%). Factor 3 (Healthcare personnel) captured fears related to communication and vulnerability, including asking “silly” questions (58.0%), exclusion from decision-making (32.8%), unfriendly staff (27.1%), and being left alone (29.0%). Factor 4 (Family life) involved fears of sexual difficulties (44.7%), relationship strain (32.4%), and childcare challenges (32.4%). Factor 5 (Cesarean section) reflected apprehension regarding surgical delivery (41.2%, Tables 3 and 4).

|

Table 2. Distribution of birth mode preference and obstetrical history among pregnant women (N = 262)

.PNG) .PNG) n= Number of respondents; %= Percentage. |

Level of fear of childbirth

Mean scores were highest for Factor 1 (17.69 ± 3.52), followed by Factor 2 (10.38 ± 2.78) and Factor 3 (9.75 ± 2.83). Lower scores were observed for Factor 4 (7.32 ± 2.34) and Factor 5 (2.29 ± 1.27), with an overall total score of 36.88 ± 10.11, indicating moderate fear (Table 5). Overall FOC scores averaged 47.45 ± 6.9 (Range: 26 - 67), with 68.3% reporting moderate fear, 21.0% high fear, and 10.7% low fear. The results also showed that FOC scores did not follow a normal distribution (K - S p = 0.011; Shapiro-Wilk p = 0.005; Table 5).

Mean scores were highest for Factor 1 (17.69 ± 3.52), followed by Factor 2 (10.38 ± 2.78) and Factor 3 (9.75 ± 2.83). Lower scores were observed for Factor 4 (7.32 ± 2.34) and Factor 5 (2.29 ± 1.27), with an overall total score of 36.88 ± 10.11, indicating moderate fear (Table 5). Overall FOC scores averaged 47.45 ± 6.9 (Range: 26 - 67), with 68.3% reporting moderate fear, 21.0% high fear, and 10.7% low fear. The results also showed that FOC scores did not follow a normal distribution (K - S p = 0.011; Shapiro-Wilk p = 0.005; Table 5).

|

Table 5. Distribution of respondents by level of fear of childbirth (N = 262)

.PNG) n= Number of respondents; %= Percentage; M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation. |

Higher FOC was significantly associated with younger maternal age (18-23 years; 30.8%) (p < 0.001), early marriage (28.6%) (p < 0.001), lower maternal education (40.0%) (p < 0.001), housewife status (29.4%) (p < 0.001), and husbands’ lower education (90.9%) or government employment (32.4%) (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). Rural residence (4.0%) (p < 0.001), primary support from spouse (18.1%) (p < 0.001), and lower family income were also linked to higher FOC (p < 0.001). These findings indicate that younger age, lower education, limited spousal support, and lower socioeconomic status are key predictors of heightened fear of childbirth.

Ordinal regression and multivariate logistic regression

Ordinal regression showed that younger maternal age (< 25 years) (AOR = 1.86; 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.03; p = 0.014), lower maternal education (AOR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.02 - 2.49; p = 0.041), husbands’ lower education (AOR = 1.71; 95% CI: 1.02 - 2.87; p = 0.043), lack of spousal support (AOR = 1.97; 95% CI: 1.19 - 3.26; p = 0.008), and non-attendance in childbirth preparation classes (AOR = 1.75; 95% CI: 1.08 - 2.84; p = 0.023) were significant predictors of higher FOC (Table 6).

In the multivariate logistic regression model, younger age (<25 years) (AOR = 2.47; 95% CI: 1.34 - 4.56; p = 0.004), lower maternal education (AOR = 2.05; 95% CI: 1.12 - 3.77; p = 0.021), husbands’ lower education (AOR = 2.28; 95% CI: 1.19 - 4.39; p = 0.012), housewife status (AOR = 1.91; 95% CI: 1.03 - 3.53; p = 0.038), rural residence (AOR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.14 - 3.66; p = 0.017), limited spousal support (AOR = 2.64; 95% CI: 1.38 - 5.06; p = 0.003), low income (≤25,000 BDT/month) (AOR = 1.95; 95% CI: 1.08 - 3.51; p = 0.026), and non-attendance in childbirth classes (AOR = 2.33; 95% CI: 1.21 - 4.49; p = 0.011) remained significant (Table 6).

Overall, younger age, low education, limited partner support, low income, and lack of prenatal class attendance were the strongest predictors of high FOC. The models demonstrated good fit (Ordinal regression: Nagelkerke R² = 0.38, χ² (8) = 76.21, p < 0.001; Logistic regression: Nagelkerke R² = 0.47, χ² (8) = 89.64, p < 0.001).

|

Table 6. Predictors of higher FOC among pregnant women (Ordinal regression an multivariate logistic regression)

.PNG) Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR); FOC (Fear of childbirth); CI = Confidence Interval; p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant; The reference categories are: age ≥25 years, higher than secondary education, employed, urban residence, adequate spousal support, family income above median, and attended childbirth classes. |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the main domains of fear of childbirth (FOC) among pregnant women and to examine the socio-demographic and obstetric factors associated with heightened fear. Our findings revealed that FOC is multifaceted, with the highest fear related to the physical process of childbirth, followed by concerns for maternal and neonatal well-being, healthcare personnel, family life, and cesarean section. Higher FOC was associated with younger age, lower education, limited spousal support, and lower socioeconomic status.

These results are consistent with a growing body of international research. In this study (6), which was a scoping review of Asian women, it was found that FOC is strongly influenced by cultural beliefs, lack of childbirth knowledge, and insufficient support, with younger and less educated women being particularly vulnerable. Their review included diverse Asian populations, highlighting the importance of context-specific interventions. Similarly, study (18) emphasized that FOC is shaped by personal beliefs, previous experiences, and perceived support, and can negatively impact maternal mental health and birth outcomes.

The relationship between childbirth beliefs and FOC was further explored by (8) in a Turkish sample, who found that negative beliefs about childbirth significantly increased fear, especially among women with limited education and support. The study (19) also reported that Turkish pregnant women with lower socioeconomic status and less access to healthcare resources experienced higher FOC, reinforcing the importance of addressing social determinants.

The prevalence and predictors of FOC have also been studied in China. The study (12) validated the Chinese version of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire and found that FOC was higher among women with less education and support. Similar study (20) used hierarchical regression analysis and identified similar predictors, including lower education, lack of information, and limited support.

Our results are further supported by systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This study (21) found that Turkish women with lower socioeconomic status and less access to healthcare resources had higher FOC. The similar study (9) reported similar findings in East African women, with younger age, lower education, and limited support being significant predictors. The study (22) studied Chinese women in late pregnancy and found that FOC was associated with lower education, lack of childbirth knowledge, and insufficient support.

Our findings regarding the protective effect of childbirth education are supported by (10), who studied Iranian primiparous women and found that regular attendance at childbirth preparation classes reduced FOC, anxiety, and depression. Their participants were grouped by class attendance, and those regularly attending reported the lowest fear and anxiety. The similar study (3) conducted a longitudinal cohort study in Sweden and found that FOC fluctuates during pregnancy and is influenced by perceived support from healthcare providers, with women reporting higher support experiencing less fear.

The study (5) examined Iranian primigravid women and found that lower education, lower income, and lack of support were associated with higher FOC, which aligns with our findings. The similar study (11) conducted qualitative research among urban Indian women and highlighted the role of social and familial expectations, as well as the impact of negative birth stories, in shaping FOC. The study (23) found that both pregnant women and their partners in Turkey experienced FOC, with communication and support from healthcare staff being key factors.

The impact of FOC on delivery preferences is also well documented. The study (16) found that higher FOC was associated with a preference for elective cesarean section among Egyptian women. This study (15) analyzed Bangladeshi data and reported that FOC and related factors contributed to higher rates of cesarean delivery. Our study similarly found that women with higher FOC were more likely to prefer cesarean section, often due to concerns about pain and complications.

A key limitation of our study is the reliance on self-reported measures, which may introduce response bias and affect the accuracy of the findings. This limitation is common in FOC research, as noted by (18) and others. Another limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of pregnant women in Bangladesh. Future studies should consider simple random sampling. Despite this, a major strength of our study is the diverse sample and systematic identification of FOC domains, which provides a nuanced understanding of the issue and supports the development of targeted, culturally appropriate interventions.

In summary, our study confirms that FOC is a complex phenomenon influenced by demographic, educational, psychosocial, and cultural factors. The findings are consistent with recent international research and highlight the need for comprehensive, multi-level strategies-including education, psychological support, and partner involvement-to reduce FOC and improve maternal well-being.

Conclusion

This study identified that fear of childbirth (FOC) among pregnant women is a multifaceted issue, with the greatest concerns centered on the physical process of childbirth, maternal and neonatal well-being, interactions with healthcare personnel, family life, and cesarean section. Our findings highlight that younger age, lower educational attainment, limited spousal support, and lower socioeconomic status are significant predictors of heightened FOC. Importantly, limited participation in childbirth preparation classes was observed among the majority of participants, and this lack of educational engagement may contribute to increased fear and anxiety surrounding childbirth. These results underscore the need for targeted interventions, such as expanding access to childbirth education and strengthening support systems, particularly for vulnerable groups. Addressing these factors through comprehensive, culturally sensitive strategies can help reduce FOC and promote better maternal mental health and birth outcomes. Future research should further explore effective approaches to increase participation in childbirth preparation and evaluate their impact on reducing FOC.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the pregnant women who participated in this study for their time and valuable insights. Special thanks are extended to the staff and management of Shariatpur Government Upazila Health Complex for their support and cooperation during data collection. We also acknowledge the contributions of our research assistants and data collectors, whose dedication made this study possible.

Funding sources

This study was self-funded, and no external funding was received.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Enam Medical College, Bangladesh (Memo No. EMC/IERB/2024/01-2). All participants were informed about the purpose and procedures of the study, and written informed consent was obtained prior to their participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the research process.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there was no competing interest.

Author contributions

The study was conceptualized and designed by HK, SH, ASL, JF, and RI. Data collection was carried out by SS, EAR, JFM, LB, ASL, and AH. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by LB, HK, JFM, ASL, and RI. The manuscript was drafted by HK, CD, JFM, JF, LB, and SA. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content was undertaken by HK, SH, JFM, JF, ASL, and LB. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the study.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Midwifery

References

1. Vaajala M, Liukkonen R, Kuitunen I, Ponkilainen V, Mattila VM, Kekki M. Factors associated with fear of childbirth in a subsequent pregnancy: a nationwide case-control analysis in Finland. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):34. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. O'Connell MA, Leahy-Warren P, Khashan AS, Kenny LC, O'Neill SM. Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(8):907-20. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Hildingsson I, Haines H, Karlström A, Nystedt A. Presence and process of fear of birth during pregnancy-Findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Women Birth. 2017;30(5):e242-7. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Mortazavi F, Agah J. Childbirth fear and associated factors in a sample of pregnant Iranian Women. Oman Med J. 2018;33(6):497-505. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Beiranvand SP, Moghadam ZB, Salsali M, Majd HA, Birjandi M, Khalesi ZB. Prevalence of fear of childbirth and its associated factors in primigravidwomen: A cross- sectional study. Shiraz E Med J. 2017;18(11):e61896. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

6. Kalok A, Kamisan Atan I, Sharip S, Safian N, Shah SA. Factors influencing childbirth fear among Asian women: a scoping review. Front Public Health. 2025:12:1448940. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Ilska M, Brandt-Salmeri A, Kołodziej-Zaleska A, Banaś E, Gelner H, Cnota W. Factors associated with fear of childbirth among Polish pregnant women. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4397. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Çubukçu B, Şahin SA. The effect of pregnant women's childbirth beliefs on fear of childbirth. Womens Stud Int Forum. 2025;108:103017. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

9. Abebe M, Tebeje TM, Yimer N, Simon T, Belete A, Melaku G, et al. Fear of childbirth and its associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Midwifery. 2024;139:104191. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Hassanzadeh R, Abbas-Alizadeh F, Meedya S, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M. Fear of childbirth, anxiety and depression in three groups of primiparous pregnant women not attending, irregularly attending and regularly attending childbirth preparation classes. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):180. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Sharma B, Jungari S, Lawange A. Factors Affecting Fear of Childbirth Among Urban Women in India: A Qualitative Study. Sage Open. 2022;12(2). [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

12. Lai THT, Kwok ST, Wang W, Seto MTY, Cheung KW. Fear of childbirth: Validation study of the Chinese version of Wijma delivery expectancy/experience questionnaire version A. Midwifery. 2022;104:103188. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Insan N, Forrest S, Jaigirdar A, Islam R, Rankin J. Social Determinants and Prevalence of Antenatal Depression among Women in Rural Bangladesh: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2364. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Azad R, Fahmi R, Shrestha S, Joshi H, Hasan M, Khan ANS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression within one year after birth in urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0215735. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Hasan F, Alam MdM, Hossain MdG. Associated factors and their individual contributions to caesarean delivery among married women in Bangladesh: analysis of Bangladesh demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):433. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Abd El-Aziz, Mansour SES, Hassan NF. Factors associated with fear of childbirth: It's effect on women's preference for elective cesarean section. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016;7(1). [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

17. Melender H-L. Experiences of Fears Associated with Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Study of 329 Pregnant Women.Birth. 2002;29(2):101-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Souto SP, Prata AP, Albuquerque RS, Caldeira S. Women's fear of childbirth during pregnancy: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2025;36(1):1628. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Gökçe İsbir G, Serçekuş P, Yenal K, Okumuş H, Durgun Ozan Y, Karabulut Ö, et al. The prevalence and associated factors of fear of childbirth among Turkish pregnant women. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2024;42(1):62-77. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Huang J, Huang J, Li Y, Liao B. The prevalence and predictors of fear of childbirth among pregnant Chinese women: a hierarchical regression analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):643. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Deliktas A, Kukulu K. Pregnant Women in Turkey Experience Severe Fear of Childbirth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(5):501-11. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. He D, Zhang J, Wang G, Huang Y, Li N, Zhu M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with fear of childbirth in late pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1589568. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Serçekuş P, Vardar O, Özkan S. Fear of childbirth among pregnant women and their partners in Turkey. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2020;24:100501. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.PNG)

.PNG)