Volume 22, Issue 4 (12-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(4): 22-27 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadeghloo E, Baniaghil A S, Roshandel G, Ghelichli M, Mehravar F, Firozbakhsh A. Quality of life in patients treated for oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Northeast Iran. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (4) :22-27

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2091-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2091-en.html

Quality of life in patients treated for oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Northeast Iran

Elaheh Sadeghloo1

, Asieh Sadat Baniaghil2

, Asieh Sadat Baniaghil2

, Gholamreza Roshandel3

, Gholamreza Roshandel3

, Maryam Ghelichli4

, Maryam Ghelichli4

, Fatemeh Mehravar5

, Fatemeh Mehravar5

, Alireza Firozbakhsh6

, Alireza Firozbakhsh6

, Asieh Sadat Baniaghil2

, Asieh Sadat Baniaghil2

, Gholamreza Roshandel3

, Gholamreza Roshandel3

, Maryam Ghelichli4

, Maryam Ghelichli4

, Fatemeh Mehravar5

, Fatemeh Mehravar5

, Alireza Firozbakhsh6

, Alireza Firozbakhsh6

1- Dental Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

3- Golestan Research Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Jorjani Clinical Sciences Research Institute, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

4- Dental Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Dental School, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,goldis.ghelichli@gmail.com

5- Ischemic Disorders Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

6- School of Medicine, Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

2- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

3- Golestan Research Center of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Jorjani Clinical Sciences Research Institute, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

4- Dental Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Dental School, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,

5- Ischemic Disorders Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

6- School of Medicine, Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

Keywords: Quality of Life, Psychological Well-Being, Oral Cancer, Head and Neck Neoplasms, Laryngeal Neoplasms, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 502 kb]

(131 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1301 Views)

Discussion

This study assessed QoL impairment in patients with oral and laryngeal carcinoma treated in Northeast Iran. The mean (68.20 ± 29.58) and median (62.50) QoL scores were below average, with about 60% of the participants experiencing mild to moderate impairment. Weight loss and feeling ill were the most severely affected domains. Eight other subdomains showed a moderate decline in QoL, including issues such as dry mouth, sticky saliva, social contacts, swallowing, pain, taste/smell, social eating, teeth problems, and speech. Additionally, four subdomains showed a mild impact on QoL, including nutritional supplements, cough, sexuality, and trismus.

Several studies have similarly reported significant QoL decline among patients with oral/tongue cancers (2,13). Systematic reviews confirm that oral cancer patients have poorer QoL than healthy individuals (12). Jehn et al. (2022) observed that during the postoperative period, patients with oral cancer may not show substantial changes in QoL over time, indicating a complex recovery process (26).

In a separate study conducted in Japan, it was found that post-treatment QoL among patients with oral cancer showed little to no improvement, emphasizing the ongoing challenges faced by these patients (14). A relatively large-scale cross-sectional study involving Chinese patients aged 18 to 92 years revealed that those with oral cancer consistently reported low QoL (11). Additionally, Breeze et al. identified a significant decline in QoL among oral cancer patients monitored over an 18-month post-treatment period, highlighting the lasting impact of the disease (27). Furthermore, laryngeal cancer also significantly affects QoL; Early-stage tumors (Stage I) were associated with significantly better QoL compared to more advanced tumors (Stages III and IV), both before and after treatment (28).

However, some studies suggest gradual post-treatment improvement (2,13). A comprehensive analysis of cross-sectional surveys conducted over 13 years among patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma indicated that three-quarters of respondents rated their QoL as good, very good, or excellent, particularly within two to ten years post-treatment. While changes between the two- and ten-year marks remained minor, some positive shifts were observed in appearance, chewing, mood, and anxiety, although swallowing abilities tended to decline. Notably, there was considerable variability in individual experiences over time, suggesting that each patient’s recovery journey may differ significantly (29).

Previous research indicates that variations in quality of life among patients with oral and laryngeal cancer can be attributed to several factors, including gender differences (19,20), age (16), tumor location (19), cancer stage (19,30), and type of treatment administered (19,31). Additionally, treatment-related side effects (19,20), the diagnostic and treatment technologies used (11), differing care requirements (8), rehabilitation care (32), and the nature and extent of complications encountered (20,26) also play significant roles. In this context, a systematic review conducted in 2022 highlighted considerable differences in research methodologies, patient demographics, tumor sites, treatment approaches, and the timing of assessments. These inconsistencies pose challenges when comparing QoL outcomes across studies (33). Overall, understanding these patterns is essential for improving care strategies and outcomes for patients with oral and laryngeal cancer. Consequently, healthcare providers are encouraged to develop comprehensive support systems that specifically address and monitor these challenges. Such initiatives are crucial for enhancing the overall quality of life for affected individuals.

This study has limitations. It was conducted at a single referral center within Golestan University of Medical Sciences, meaning the results may not be generalizable to the broader Iranian population. The cross-sectional design assessed QoL at a single time point, preventing evaluation of long-term changes. Further research is needed among diverse cancer populations.

Conclusion

The study indicates that QoL among participants with oral and laryngeal SCC was below the threshold. Most reported mild to moderate QoL impairments, including pain, swallowing difficulty, taste and smell issues, speech problems, social and dietary challenges, sexual concerns, dental problems, trismus, dry mouth, sticky saliva, cough, feeling ill, and weight loss. These symptoms substantially reduce QoL. Interventions should focus on symptom management and patient empowerment to help individuals regain a greater sense of control over their challenges and improve overall QoL. Health professionals can use the results of this study to gain a deeper understanding of patients’ QoL. The findings provide valuable insights for healthcare workers and policymakers to enhance QoL programs.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank all participants who completed the questionnaire and contributed their time to this study.

We also thank the Research and Technology Deputy of Golestan University of Medical Sciences for supporting this study (Grant No. 112366).

Funding sources

No funding was received for this study.

Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1400.276) approved the study protocol. The study involved minimal risk and no invasive procedures. It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics. The participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage and were assured that the information collected would remain confidential and be used solely for research purposes. In addition, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

E.S., M.GH., AS.B., and GR.R. conceptualized the study design. E.S. and M.GH. conducted the study. A.R.F. entered and cleaned the data. GR.R. and F.M. F.M. analyzed the data. F.M. and A.S.B. interpreted the findings. A.S.B. drafted the manuscript, and A.S.B. and F.M. revised it. All authors read and approved the final version.

Data availability statement

Due to participant consent terms, datasets generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available but can be requested from the corresponding author.

Full-Text: (33 Views)

Introduction

Global statistics revealed nearly 20 million new cancer diagnoses and approximately 10 million cancer-related deaths in 2022. Projections indicate that by 2050, demographic shifts could raise the number of new annual cancer cases to 35 million, a 77% increase compared to 2022 figures (1). Cancers of the oral cavity (2) and larynx (3) are among the most common worldwide, with most (94.53%) classified as squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) (3). Researchers and health professionals must therefore focus on the quality of life (QoL) challenges faced by these patients.

Patients with oral and laryngeal cancer often experience numerous challenges that can significantly affect their QoL, with many of these difficulties persisting long after treatment (4). QoL encompasses a holistic view of an individual’s or population’s well-being, accounting for both positive and negative aspects of their experiences at a specific time (5). Regular QoL assessments should be integrated into ongoing patient evaluations (6). Multidisciplinary healthcare teams need to prioritize patients’ QoL while balancing this with their medical needs (5).

Oral and/or laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma often reduces patients’ QoL (2). This decline may persist for a long period, even after treatment has ended (4). Various factors contribute to this issue, including fatigue (2), pain, appearance-related concerns, mood problems (7), elevated anxiety, social difficulties (2), speech problems (3), challenges with eating in social settings (8), taste disturbances (7), limited mouth opening, dental issues, impaired chewing ability, trismus (8,9), reduced saliva production (7), dry mouth, thickened saliva (8), swallowing difficulties (7), dysphagia with solid foods (8), and decreased nutritional intake (2). Financial challenges, such as treatment costs and loss of employment during therapy, may also affect compliance (2). Wang et al. reported that four oral cancer-related symptoms, including trouble with social contacts, swallowing problems, teeth problems, and feeling ill, were significantly associated with greater care needs and lower QoL among oral cancer patients (8). Similarly, a qualitative ethnographic study of laryngeal cancer patients identified four QoL-related subcategories: difficulty eating, giving up some foods, loss of pleasure, and problems preparing food (10). Thus, identifying QoL impairment is an essential goal of healthcare and a significant factor in monitoring treatment and therapeutic outcomes in cancer patients (11).

A systematic review indicated that oral cancer patients experience significantly poorer QoL compared to healthy individuals (12). However, another study found that QoL tends to improve and gradually return to baseline over time after treatment (13). Conversely, a Japanese study reported no improvement in QoL following treatment for oral cancer (14). These findings suggest the need for comprehensive support systems to address and monitor QoL issues among cancer patients.

While several studies have explored QoL in cancer patients, few have specifically focused on oral and laryngeal cancer (15). Onagh et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review in 2022 (16) and analyzed the QoL of cancer patients in general. They found that out of 30 studies conducted in Iran, only one study explicitly focused on head and neck cancers. Given the significance of QoL, the prevalence of oral and laryngeal cancers, and the scarcity of research in this area, further investigation is essential. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the QoL of patients with oral and laryngeal cancer treated in Golestan Province, Iran, in 2022.

Methods

Design and participant

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 2022 in Golestan Province, Iran, among 54 participants with a history of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. All patients over 18 years old registered between 2011 and 2016 in the Liver and Digestive Research Centre registry at Golestan University of Medical Sciences who had undergone treatment were included through non-probability sampling. Individuals with disease recurrence, relapse, or those receiving neoadjuvant therapy, or unwilling to participate, were excluded. Golestan Province, located in northeast Iran, is one of the country’s 31 provinces. According to the 2016 census in Iran, it has a population of 1,868,819 and includes 14 counties.

The sample size was determined based on the total number of eligible patients diagnosed with oral and laryngeal SCC who received primary treatment at the tertiary referral center’s otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery departments. Given the specific inclusion criteria and the relatively low prevalence of these cancers, census sampling was used, yielding 54 patients. This sample size aligns with similar single-center QoL studies in head and neck cancer populations (17) and is sufficient to provide meaningful insights into the QOL landscape of this group. All eligible patients who provided informed consent were enrolled to maximize representativeness.

Data collection

Data were gathered using two instruments: a demographic information form and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Head and Neck 35 (EORTC QLQ-H&N35).

The EORTC QLQ-H&N35, developed in 1999 (18), includes seven subscales: pain (4 items), swallowing (4 items), taste and smell (2 items), speech (3 items), social eating (4 items), sexuality (2 items), and social contacts (5 items), as well as 11 single items addressing issues such as teeth problems, dry mouth, cough, trismus, sticky saliva, weight loss/gain, nutritional supplements, feeding tubes, feeling ill, and painkiller use (19).

Items 1 to 30 are rated on a 4-point Likert scale with “not at all,” “a little,” “quite a lot,” and “very much,” scored 1 to 4, respectively. Items 31 to 35 (Painkillers, nutritional supplements, feeding tubes, weight loss, and weight gain) use binary “yes” (2) or “no” (1) responses (19). The questionnaire does not employ reverse scoring, and higher scores indicate lower QoL (20,21). Sipilä et al. (22) reported that the raw score range for this tool is between 35 and 130, with a mean of 82.5 serving as the threshold in this study.

The mean total QoL score, derived from the trance score (0-100) on the numerical rating scale, was categorized as normal (0-25), mild (26-50), moderate (51-75), and severe (76-100) (23). For global health and functional scales, QoL impairment was classified inversely: normal (76-100), mild (51-75), moderate (26-50), and severe (0-25). Since the symptom scale in the original EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 has a reversed scoring system, QoL impairment is categorized as follows: normal (0-25), mild (26-50), moderate (51-75), and severe (76-100).

The questionnaire's psychometric properties were first developed in 1992, later revised to include the H&N35 module, and officially validated in 1999 (18). A recent systematic review reported that studies using the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 were conducted in 28 countries, with the questionnaire validated in 21 languages (24). The Persian version of the EORTC QLQ-H&N has also been validated by its original developer, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (25).

The demographic form included age, gender, place of residence, county, cancer site (Mouth or larynx), age at diagnosis, and year of treatment. Contact details were obtained from the Golestan Liver and Digestive Research Centre’s database. The researcher (ES) conducted phone interviews, explained the study objectives to the participants, and assured them of confidentiality. The participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained from all participants; none were under 16 years old.

Of 283 names registered at the Liver and Digestive Research Centre, 140 individuals answered phone calls, while 143 did not. Of them, five declined participation, and 81 (28.6%) had died. Ultimately, 54 participants were enrolled (Figure 1).

Global statistics revealed nearly 20 million new cancer diagnoses and approximately 10 million cancer-related deaths in 2022. Projections indicate that by 2050, demographic shifts could raise the number of new annual cancer cases to 35 million, a 77% increase compared to 2022 figures (1). Cancers of the oral cavity (2) and larynx (3) are among the most common worldwide, with most (94.53%) classified as squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) (3). Researchers and health professionals must therefore focus on the quality of life (QoL) challenges faced by these patients.

Patients with oral and laryngeal cancer often experience numerous challenges that can significantly affect their QoL, with many of these difficulties persisting long after treatment (4). QoL encompasses a holistic view of an individual’s or population’s well-being, accounting for both positive and negative aspects of their experiences at a specific time (5). Regular QoL assessments should be integrated into ongoing patient evaluations (6). Multidisciplinary healthcare teams need to prioritize patients’ QoL while balancing this with their medical needs (5).

Oral and/or laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma often reduces patients’ QoL (2). This decline may persist for a long period, even after treatment has ended (4). Various factors contribute to this issue, including fatigue (2), pain, appearance-related concerns, mood problems (7), elevated anxiety, social difficulties (2), speech problems (3), challenges with eating in social settings (8), taste disturbances (7), limited mouth opening, dental issues, impaired chewing ability, trismus (8,9), reduced saliva production (7), dry mouth, thickened saliva (8), swallowing difficulties (7), dysphagia with solid foods (8), and decreased nutritional intake (2). Financial challenges, such as treatment costs and loss of employment during therapy, may also affect compliance (2). Wang et al. reported that four oral cancer-related symptoms, including trouble with social contacts, swallowing problems, teeth problems, and feeling ill, were significantly associated with greater care needs and lower QoL among oral cancer patients (8). Similarly, a qualitative ethnographic study of laryngeal cancer patients identified four QoL-related subcategories: difficulty eating, giving up some foods, loss of pleasure, and problems preparing food (10). Thus, identifying QoL impairment is an essential goal of healthcare and a significant factor in monitoring treatment and therapeutic outcomes in cancer patients (11).

A systematic review indicated that oral cancer patients experience significantly poorer QoL compared to healthy individuals (12). However, another study found that QoL tends to improve and gradually return to baseline over time after treatment (13). Conversely, a Japanese study reported no improvement in QoL following treatment for oral cancer (14). These findings suggest the need for comprehensive support systems to address and monitor QoL issues among cancer patients.

While several studies have explored QoL in cancer patients, few have specifically focused on oral and laryngeal cancer (15). Onagh et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review in 2022 (16) and analyzed the QoL of cancer patients in general. They found that out of 30 studies conducted in Iran, only one study explicitly focused on head and neck cancers. Given the significance of QoL, the prevalence of oral and laryngeal cancers, and the scarcity of research in this area, further investigation is essential. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the QoL of patients with oral and laryngeal cancer treated in Golestan Province, Iran, in 2022.

Methods

Design and participant

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in 2022 in Golestan Province, Iran, among 54 participants with a history of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. All patients over 18 years old registered between 2011 and 2016 in the Liver and Digestive Research Centre registry at Golestan University of Medical Sciences who had undergone treatment were included through non-probability sampling. Individuals with disease recurrence, relapse, or those receiving neoadjuvant therapy, or unwilling to participate, were excluded. Golestan Province, located in northeast Iran, is one of the country’s 31 provinces. According to the 2016 census in Iran, it has a population of 1,868,819 and includes 14 counties.

The sample size was determined based on the total number of eligible patients diagnosed with oral and laryngeal SCC who received primary treatment at the tertiary referral center’s otorhinolaryngology and head and neck surgery departments. Given the specific inclusion criteria and the relatively low prevalence of these cancers, census sampling was used, yielding 54 patients. This sample size aligns with similar single-center QoL studies in head and neck cancer populations (17) and is sufficient to provide meaningful insights into the QOL landscape of this group. All eligible patients who provided informed consent were enrolled to maximize representativeness.

Data collection

Data were gathered using two instruments: a demographic information form and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Head and Neck 35 (EORTC QLQ-H&N35).

The EORTC QLQ-H&N35, developed in 1999 (18), includes seven subscales: pain (4 items), swallowing (4 items), taste and smell (2 items), speech (3 items), social eating (4 items), sexuality (2 items), and social contacts (5 items), as well as 11 single items addressing issues such as teeth problems, dry mouth, cough, trismus, sticky saliva, weight loss/gain, nutritional supplements, feeding tubes, feeling ill, and painkiller use (19).

Items 1 to 30 are rated on a 4-point Likert scale with “not at all,” “a little,” “quite a lot,” and “very much,” scored 1 to 4, respectively. Items 31 to 35 (Painkillers, nutritional supplements, feeding tubes, weight loss, and weight gain) use binary “yes” (2) or “no” (1) responses (19). The questionnaire does not employ reverse scoring, and higher scores indicate lower QoL (20,21). Sipilä et al. (22) reported that the raw score range for this tool is between 35 and 130, with a mean of 82.5 serving as the threshold in this study.

The mean total QoL score, derived from the trance score (0-100) on the numerical rating scale, was categorized as normal (0-25), mild (26-50), moderate (51-75), and severe (76-100) (23). For global health and functional scales, QoL impairment was classified inversely: normal (76-100), mild (51-75), moderate (26-50), and severe (0-25). Since the symptom scale in the original EORTC-QLQ-H&N35 has a reversed scoring system, QoL impairment is categorized as follows: normal (0-25), mild (26-50), moderate (51-75), and severe (76-100).

The questionnaire's psychometric properties were first developed in 1992, later revised to include the H&N35 module, and officially validated in 1999 (18). A recent systematic review reported that studies using the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 were conducted in 28 countries, with the questionnaire validated in 21 languages (24). The Persian version of the EORTC QLQ-H&N has also been validated by its original developer, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (25).

The demographic form included age, gender, place of residence, county, cancer site (Mouth or larynx), age at diagnosis, and year of treatment. Contact details were obtained from the Golestan Liver and Digestive Research Centre’s database. The researcher (ES) conducted phone interviews, explained the study objectives to the participants, and assured them of confidentiality. The participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained from all participants; none were under 16 years old.

Of 283 names registered at the Liver and Digestive Research Centre, 140 individuals answered phone calls, while 143 did not. Of them, five declined participation, and 81 (28.6%) had died. Ultimately, 54 participants were enrolled (Figure 1).

.PNG) Figure 1. Flowchart of participant inclusion in the study |

QoL scores and subdomains were analyzed using means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions in SPSS version 21. The point prevalence of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in the 14 counties of Golestan Province was calculated as the number of diagnosed cases per 100,000 people in each county at a specific point in time.

Results

Half of the participants were under 50 years old, with a predominantly male distribution. Laryngeal SCC (55.6%) was more prevalent than oral SCC (44.4%). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The point prevalence of oral and laryngeal SCC across the 14 counties in Golestan Province was 15.14 per 100,000, ranging from 5.80 to 26.01. Higher rates were observed in Bandargaz (26.01%), Gorgan (22.27%), and Kordkoy (21.04%) counties (Table 2).

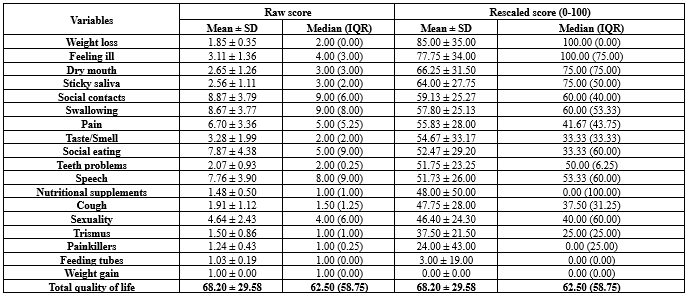

The mean and median QoL scores were 68.20 ± 29.58 and 62.50, respectively (Table 3).

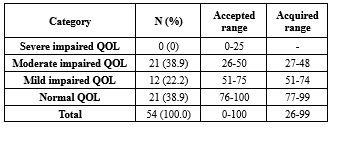

Overall, 38.9% of the participants had normal QoL, 22.2% mild impairment, and 38.9% moderate impairment; none had severe impairment (Table 4).

Subdomain analysis of the mean based on trance scores revealed severe impairment in weight loss (85.00 ± 35.00) and feeling ill (77.75 ± 34.00). Moderate impairments were observed in dry mouth (66.25 ± 31.50), sticky saliva (64.00 ± 27.75), social contacts (59.13 ± 25.27), swallowing (57.80 ± 25.13), pain (55.83 ± 28.00), taste/smell (54.67 ± 33.17), social eating (52.47 ± 29.20), teeth problems (51.75 ± 23.25), and speech (51.73 ± 26.00). Mild impairments were found in nutritional supplements (48.00 ± 50.00), cough (47.75 ± 28.00), sexuality (46.40 ± 24.30), and trismus (37.50 ± 21.50). Painkillers (24.00 ± 43.00), feeding tubes (3.00 ± 19.00), and weight gain (0.00 ± 0.00) domains were within normal limits (Table 3).

Results

Half of the participants were under 50 years old, with a predominantly male distribution. Laryngeal SCC (55.6%) was more prevalent than oral SCC (44.4%). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

The point prevalence of oral and laryngeal SCC across the 14 counties in Golestan Province was 15.14 per 100,000, ranging from 5.80 to 26.01. Higher rates were observed in Bandargaz (26.01%), Gorgan (22.27%), and Kordkoy (21.04%) counties (Table 2).

The mean and median QoL scores were 68.20 ± 29.58 and 62.50, respectively (Table 3).

Overall, 38.9% of the participants had normal QoL, 22.2% mild impairment, and 38.9% moderate impairment; none had severe impairment (Table 4).

Subdomain analysis of the mean based on trance scores revealed severe impairment in weight loss (85.00 ± 35.00) and feeling ill (77.75 ± 34.00). Moderate impairments were observed in dry mouth (66.25 ± 31.50), sticky saliva (64.00 ± 27.75), social contacts (59.13 ± 25.27), swallowing (57.80 ± 25.13), pain (55.83 ± 28.00), taste/smell (54.67 ± 33.17), social eating (52.47 ± 29.20), teeth problems (51.75 ± 23.25), and speech (51.73 ± 26.00). Mild impairments were found in nutritional supplements (48.00 ± 50.00), cough (47.75 ± 28.00), sexuality (46.40 ± 24.30), and trismus (37.50 ± 21.50). Painkillers (24.00 ± 43.00), feeding tubes (3.00 ± 19.00), and weight gain (0.00 ± 0.00) domains were within normal limits (Table 3).

|

Table 1. Selected characteristics of individuals with a history of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Golestan Province (n = 54)

.PNG) |

|

Table 2. The point prevalence of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma in 14 counties of Golestan province based on Iran’s population and the housing census 2022 (n= 283)

.PNG) Table 3. Raw and rescaled scores of the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 scales for patients with a history of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 54)  For dichotomous variables (Yes/No), such as Painkillers, scoring is typically done as No = 1 and Yes = 2. Therefore, the rescaled score is calculated using the formula: (Raw score - 1) * 100. This results in a “No” score of 0 and a “Yes” score of 100. The median and IQR for these items may appear unusual due to their binary nature (For example, a median of 1 or 2, which, after rescaling, becomes 0 or 100, respectively). |

|

Table 4. The absolute and relative frequency of impaired QOL severity among individuals with a history of oral and laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 54)

|

Discussion

This study assessed QoL impairment in patients with oral and laryngeal carcinoma treated in Northeast Iran. The mean (68.20 ± 29.58) and median (62.50) QoL scores were below average, with about 60% of the participants experiencing mild to moderate impairment. Weight loss and feeling ill were the most severely affected domains. Eight other subdomains showed a moderate decline in QoL, including issues such as dry mouth, sticky saliva, social contacts, swallowing, pain, taste/smell, social eating, teeth problems, and speech. Additionally, four subdomains showed a mild impact on QoL, including nutritional supplements, cough, sexuality, and trismus.

Several studies have similarly reported significant QoL decline among patients with oral/tongue cancers (2,13). Systematic reviews confirm that oral cancer patients have poorer QoL than healthy individuals (12). Jehn et al. (2022) observed that during the postoperative period, patients with oral cancer may not show substantial changes in QoL over time, indicating a complex recovery process (26).

In a separate study conducted in Japan, it was found that post-treatment QoL among patients with oral cancer showed little to no improvement, emphasizing the ongoing challenges faced by these patients (14). A relatively large-scale cross-sectional study involving Chinese patients aged 18 to 92 years revealed that those with oral cancer consistently reported low QoL (11). Additionally, Breeze et al. identified a significant decline in QoL among oral cancer patients monitored over an 18-month post-treatment period, highlighting the lasting impact of the disease (27). Furthermore, laryngeal cancer also significantly affects QoL; Early-stage tumors (Stage I) were associated with significantly better QoL compared to more advanced tumors (Stages III and IV), both before and after treatment (28).

However, some studies suggest gradual post-treatment improvement (2,13). A comprehensive analysis of cross-sectional surveys conducted over 13 years among patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma indicated that three-quarters of respondents rated their QoL as good, very good, or excellent, particularly within two to ten years post-treatment. While changes between the two- and ten-year marks remained minor, some positive shifts were observed in appearance, chewing, mood, and anxiety, although swallowing abilities tended to decline. Notably, there was considerable variability in individual experiences over time, suggesting that each patient’s recovery journey may differ significantly (29).

Previous research indicates that variations in quality of life among patients with oral and laryngeal cancer can be attributed to several factors, including gender differences (19,20), age (16), tumor location (19), cancer stage (19,30), and type of treatment administered (19,31). Additionally, treatment-related side effects (19,20), the diagnostic and treatment technologies used (11), differing care requirements (8), rehabilitation care (32), and the nature and extent of complications encountered (20,26) also play significant roles. In this context, a systematic review conducted in 2022 highlighted considerable differences in research methodologies, patient demographics, tumor sites, treatment approaches, and the timing of assessments. These inconsistencies pose challenges when comparing QoL outcomes across studies (33). Overall, understanding these patterns is essential for improving care strategies and outcomes for patients with oral and laryngeal cancer. Consequently, healthcare providers are encouraged to develop comprehensive support systems that specifically address and monitor these challenges. Such initiatives are crucial for enhancing the overall quality of life for affected individuals.

This study has limitations. It was conducted at a single referral center within Golestan University of Medical Sciences, meaning the results may not be generalizable to the broader Iranian population. The cross-sectional design assessed QoL at a single time point, preventing evaluation of long-term changes. Further research is needed among diverse cancer populations.

Conclusion

The study indicates that QoL among participants with oral and laryngeal SCC was below the threshold. Most reported mild to moderate QoL impairments, including pain, swallowing difficulty, taste and smell issues, speech problems, social and dietary challenges, sexual concerns, dental problems, trismus, dry mouth, sticky saliva, cough, feeling ill, and weight loss. These symptoms substantially reduce QoL. Interventions should focus on symptom management and patient empowerment to help individuals regain a greater sense of control over their challenges and improve overall QoL. Health professionals can use the results of this study to gain a deeper understanding of patients’ QoL. The findings provide valuable insights for healthcare workers and policymakers to enhance QoL programs.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank all participants who completed the questionnaire and contributed their time to this study.

We also thank the Research and Technology Deputy of Golestan University of Medical Sciences for supporting this study (Grant No. 112366).

Funding sources

No funding was received for this study.

Ethical statement

The Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.GOUMS.REC.1400.276) approved the study protocol. The study involved minimal risk and no invasive procedures. It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the guidelines of the Committee on Publication Ethics. The participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage and were assured that the information collected would remain confidential and be used solely for research purposes. In addition, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

E.S., M.GH., AS.B., and GR.R. conceptualized the study design. E.S. and M.GH. conducted the study. A.R.F. entered and cleaned the data. GR.R. and F.M. F.M. analyzed the data. F.M. and A.S.B. interpreted the findings. A.S.B. drafted the manuscript, and A.S.B. and F.M. revised it. All authors read and approved the final version.

Data availability statement

Due to participant consent terms, datasets generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available but can be requested from the corresponding author.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Management and Health System

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229-63. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

2. Lavdaniti M, Tilaveridis I, Palitzika D, Kyrgidis A, Triaridis S, Vachtsevanos K, et al. Quality of Life in Oral Cancer Patients in Greek Clinical Practice: A Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(23):7235. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

3. Koroulakis A, Agarwal M. Laryngeal Cancer. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Taylor KJ, Amdal CD, Bjordal K, Astrup GL, Herlofson BB, Duprez F, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors: A large multinational study. Int J Cancer. 2024;154(10):1772-85. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Teoli D, Bhardwaj A. Quality of Life. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

6. Angastiniotis M, Fung EB. LIFESTYLE AND QUALITY OF LIFE. In: Taher AT, Farmakis D, Porter JB, Cappellini MD, Musallam KM, editors. Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassaemia (TDT). Nicosia (Cyprus): Thalassaemia International Federation;2025. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Sanabria A, Sánchez D, Chala A, Alvarez A. Quality of life in patients with larynx cancer in Latin America: Comparison between laryngectomy and organ preservation protocols. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018;97(3):83-90. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Wang T-F, Li Y-J, Chen L-C, Chou C, Yang S-C. Correlation Between Postoperative Health-Related Quality of Life and Care Needs of Oral Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(1):12-21. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Vermaire JA, Partoredjo ASK, de Groot RJ, Brand HS, Speksnijder CM. Mastication in health-related quality of life in patients treated for oral cancer: A systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31(6):e13744. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

10. Cipriano-Crespo C, Conde-Caballero D, Rivero Jiménez B, Mariano-Juárez L. Eating experiences and quality of life in patients with larynx cancer in Spain. A qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2021;16(1):1967262. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

11. Zhang Y, Cui C, Wang Y, Wang L. Effects of stigma, hope and social support on quality of life among Chinese patients diagnosed with oral cancer: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):112. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

12. Yuwanati M, Gondivkar S, Sarode SC, Gadbail A, Desai A, Mhaske S, et al. Oral health-related quality of life in oral cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2021;17(8):979-90. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

13. Palitzika D, Tilaveridis I, Lavdaniti M, Vahtsevanos K, Kosintzi A, Antoniades K. Quality of Life in Patients With Tongue Cancer After Surgical Treatment: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22511. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

14. Aoki T, Ota Y, Sasaki M, Suzuki T, Uchibori M, Nakanishi Y, et al. Quality of life of Japanese elderly oral cancer patients during the perioperative period. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;50(9):1138-46. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Aoki T, Ota Y, Suzuki T, Denda Y, Aoyama K-I, Akiba T, et al. Longitudinal changes in the quality of life of oral cancer patients during the perioperative period. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(6):1038-45. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Onagh MN, Behnampour N, Mirzaei F, Asghari N, Zokaee H. Quality of Life in Head and Neck Cancer Patients with Xerostomia due to Radiotherapy. J Res Dent Sci. 2021;18(1):57-66. [View at Publisher] [DOI]

17. Lindell E, Kollén L, Johansson M, Karlsson T, Rydén L, Fässberg MM, et al. Dizziness and health-related quality of life among older adults in an urban population: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):231. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, De Graeff A, Boysen M, Evensen JF, et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(3):1008-19. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

19. Hashemipour MA, Pooyafard A, Navabi N, Kakoie S, Rahbanian N. Quality of life in Iranian patients with head-and-neck cancer. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:358. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. Sadri D, Bahraminezhad Y. Evaluating the Quality of Life in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and the Associated Factors in those Referring to Imam Khomeini Cancer Institute, 2012. J Res Dent Sci. 2014;11(3):181-6. [View at Publisher]

21. Torabi M, Jahanian B, Afshar MK. Quality of life in Iranian patients with oral and head and neck cancer. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2021;21:e0062-e. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

22. Sipilä M, Kiukas E-L, Lindford A, Ylä-Kotola T, Lauronen J, Sintonen H, Lassus P. Systematic patient Selection criteria for face transplantation [thesis]. Helsinki: University of Helsinki; 2020. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

23. Saini J, Bakshi J, Panda NK, Sharma M, Vir D, Goyal AK. Cut-off points to classify numeric values of quality of life into normal, mild, moderate, and severe categories: an update for EORTC-QLQ-H&N35. The Egyptian Journal of Otolaryngology. 2024;40(1):83. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

24. Parkar S, Sharma A. Validation of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer head and neck cancer quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) across languages: A systematic review. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 3):6100-7.

PMid:36742587 PMCid:PMC9895643 [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EORTC QLQ-HN35 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 27]. Available from: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/qlq-hn35/ [View at Publisher]

26. Jehn P, Spalthoff S, Lentge F, Zeller A-N, Tavassol F, Neuhaus M-T, et al. Postoperative quality of life and therapy-related impairments of oral cancer in relation to time-distance since treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(6):1366-78. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Breeze J, Rennie A, Dawson D, Tipper J, Rehman K-U, Grew N, et al. Patient-reported quality of life outcomes following treatment for oral cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47(3):296-301. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

28. Murariu MO, Boia ER, Horhat DI, Mot CI, Balica NC, Trebuian CI, et al. Psychological Well-Being and Quality of Life in Laryngeal Cancer Patients across Tumor. J Clin Med. 2024;13(20):6138. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

29. Rogers SN, Lowe D. Health-related quality of life after oral cancer treatment: 10-year outcomes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol.

2020;130(2):144-9. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

30. Dános K, Tamás L. [Overall survival, organ preservation, function preservation: the role of surgery in the treatment of laryngeal cancer]. Magy Onkol. 2025;69(2):129-33. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

31. Fuereder T, Kocher F, Vermorken JB. Systemic therapy for laryngeal carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1541385. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

32. Li N, Guo W, Hu Z, Huang Z, Huang J. Exploration of a remote swallowing training model after laryngeal cancer surgery: Non-randomized concurrent controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2025:1357633x251331131. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

33. Vermaire JA, Partoredjo ASK, de Groot RJ, Brand HS, Speksnijder CM. Mastication in health‐related quality of life in patients treated for oral cancer: A systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2022;31(6):e13744. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |