Volume 22, Issue 3 (9-2025)

J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025, 22(3): 58-64 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Baniaghil A S, Amini K, Behnampour N. Prevalence of domestic violence among Iranian couples in Gorgan, Northern Iran, in 2022. J Res Dev Nurs Midw 2025; 22 (3) :58-64

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2018-en.html

URL: http://nmj.goums.ac.ir/article-1-2018-en.html

1- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,kosaramini97@gmail.com

3- Health Management and Social Development Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

2- Counseling and Reproductive Health Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran ,

3- Health Management and Social Development Research Center, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran

Keywords: Domestic violence, Intimate partner violence, Perpetrator of violence, Victim of violence, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 513 kb]

(63 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (350 Views)

Discussion

This study, conducted in Gorgan, northeastern Iran, investigated the prevalence of domestic violence among couples over the past year. The findings revealed that nearly 50% of couples experienced some form of domestic violence. Specifically, unidirectional violence was reported by more than half of the participants, with a higher prevalence of MFPV (19.6%) compared to FMPV (7.5%). Bidirectional violence was reported in less than 50% of cases. A broader analysis, combining both unidirectional and bidirectional incidents, showed that over the past year, 32.5% of males and 44.6% of females had experienced domestic violence. The prevalence of psychological aggression and sexual coercion was notably higher, whereas the incidence of physical abuse, such as assault and injury, was less frequent.

The study found that 52% of couples had experienced domestic violence in the past year. This finding is a concerning statistic but is notably lower than the 81% prevalence reported in a study in 2018 on the Iranian population (13). This discrepancy could be attributed to a variety of factors, including differences in cultural attitudes, knowledge, demographic characteristics, and reporting behaviors related to domestic violence. Although increased awareness may have contributed to the lower rate observed in the present study, the prevalence remains alarming. Further research is necessary to fully understand domestic violence and to develop effective prevention strategies.

Based on the findings of the current research, 44.6% of females reported experiencing domestic violence. Findings align with a broader body of research that highlights the high prevalence of domestic violence against females globally. For instance, a notable report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that approximately one-third of females living with a male partner have been victimized by their cohabitants (4). A study from southern Iran revealed that 64.1% of female participants reported experiencing domestic violence in the preceding year (14). In a broader context, a systematic review conducted in 2023 highlighted the notable variability in the lifetime prevalence of domestic violence across developing countries, with figures ranging from 29.4% to 73.78% (15). Additionally, a meta-analysis focusing on Iranian females estimated the overall prevalence of violence against them to be 58% (16). In Garmsar, Iran, a study revealed that 56.11% of females had been exposed to violence. This finding highlights the significant global variation in domestic violence rates against females, which are shaped by diverse cultural, social, and economic factors (17). Further research conducted in Kerman, Iran, in 2023 utilized the Network Scale-Up method to estimate that the mean rate of domestic violence against females in the region was approximately 44%. However, the visibility of these incidents, when measured through a direct method, was only 33%, indicating that nearly two-thirds go unreported, likely due to the significant stigma associated with the issue (14). Furthermore, in Ethiopia, 33.5% of married females reported experiencing domestic violence within the past year (18). These findings highlight a critical need for sustained global awareness and intervention efforts to combat domestic violence.

In this study, the prevalence of domestic violence among males was reported at 32.5%. A separate study conducted on married Turkish males found that 57% admitted to perpetrating violence against their wives. A significant portion of these males had a history of experiencing domestic violence during childhood and witnessing violence against females in their formative years (19). The experience of witnessing inter-parental violence and being a victim of child abuse were identified as direct contributing factors to their own victimization as adults (20,21). However, scholarly research on domestic violence against males remains scarce. Male victims of IPV often report feelings of shame and confusion, as their experiences contradict conventional societal norms and expectations of masculinity (22).

The prevalence of domestic violence significantly varies by region and type of abuse. A notable finding, derived from direct measurement methods, indicates an annual prevalence of 60.9% for psychological violence. In comparison, the documented rates for physical and sexual violence are 34.7% and 37.7%, respectively (15). A study from Ethiopia reported high rates of domestic violence, with psychological abuse being the most common at 43.8%, followed by physical violence (28.9%) and sexual violence (19.1%) (18). Similarly, research in Southeast Iran found a high annual prevalence of psychological violence (60.9%), alongside physical violence (34.7%) and sexual violence (37.7%) (14). Based on a comprehensive meta-analysis, the prevalence of domestic violence is reported as follows: Physical violence at approximately 25%, psychological or mental violence at 50%, and sexual violence at 20% (16). Furthermore, a systematic review focusing on the Middle East found that psychological abuse was the most prevalent form, with an occurrence rate of 48.6%. Rates of other forms of abuse were also found to be substantial, including physical abuse (28.4%), sexual violence (18.5%), and injury-related violence (18.4%) (23). These results highlight the pervasive nature of domestic violence, especially psychological abuse, and emphasize the critical need for targeted interventions and support systems for affected individuals in various regions.

This study's findings indicate that among couples who experienced violence within a one-year period, less than 50% involved bidirectional violence. The prevalence of MFPV was 19.6%, while FMPV was 7.5%. These results align with the family systems theory, which posits that the behavior of family members is mutually influential (24). They also challenge the conventional view that IPV is exclusively perpetrated by aggressive males against vulnerable females. This stereotype profoundly affects individuals’ decisions to seek help and influences how service providers respond (25). A systematic review revealed that bidirectional violence is the most prevalent form of violence, occurring regardless of an individual's sex or sexual orientation (26). Despite past research indicating that bidirectional violence is a common pattern, there is a lack of understanding regarding how societal stereotypes and attitudes are expressed when both partners in a relationship are simultaneously in the roles of victim and perpetrator (25). This highlights the need for gender-inclusive services tailored to the specific needs of males, requiring greater recognition, awareness, and resource allocation (27). As Houseman et al. observed, violence is a cyclical phenomenon, with victims living in persistent fear of future incidents. It is a universal issue, transcending cultural, racial, religious, and socioeconomic boundaries within intimate relationships. Although couples may desire an end to the violence, such hope is often unfounded (4).

Based on the study's findings, psychological aggression (Occurring 11-20 times per year) and sexual coercion (Occurring 6-10 times per year) were identified as the most prevalent forms of violence. It is crucial to recognize that the cycle of violence often initiates with verbal threats before escalating to physical aggression. Violent incidents are typically unpredictable, and their underlying triggers are frequently obscure. The perpetrator may demonstrate increased judgmental attitudes, irritability, and volatility, ultimately culminating in an explosive phase. During this phase, the victim may try to de-escalate the situation by pacifying the abuser, maintaining physical distance, or engaging in logical reasoning, often with little success. The explosive phase can prompt the victim to take protective measures for themselves and their family, which frequently results in injury. Subsequently, a "honeymoon phase" may occur, during which the victim might seek counseling and medical assistance and may even agree to discontinue legal actions (4).

This study's use of self-administered questionnaires to collect data on domestic violence over a one-year recall period may have introduced recall bias. Additionally, the social stigma associated with family reputation in Iran could lead to the underreporting of domestic violence. While participants completed the instruments separately, the responses of one partner might still have been influenced by the other's awareness or participation in the study.

Conclusion

This study revealed that nearly half of the couples surveyed experienced some form of violence, with males reporting a higher prevalence than females. The most common forms of violence were verbal and sexual. These findings help healthcare professionals enhance their knowledge and improve the implementation of domestic violence prevention and screening programs. Additionally, the results offer valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to develop effective strategies to prevent and address domestic violence, with a specific focus on household dynamics, roles, and gender. The results also emphasize the importance of acknowledging domestic violence against males and the necessity for targeted screening programs to safeguard their mental health, particularly by sexual health policymakers. Future research is needed to identify effective interventions for reducing domestic violence and fostering healthy relationships.

Acknowledgement

This study is derived from a master's thesis in Midwifery Counseling at the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, titled "Domestic Violence and Resilience in Couples, Gorgan, Iran, in 2022." The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Golestan University of Medical Sciences for their sincere support, the leadership and staff of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery for facilitating the research, and all participating couples.

Funding sources

This study was financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 112434).

Ethical statement

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.099) on June 12, 2022. The research was conducted in full accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were 16 years of age or older. Online written informed consent was obtained from every participant after providing full explanations on the research objectives, voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participant privacy was protected by ensuring the confidentiality of their data.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: A.S.B., K.A., and B.N. Data collection: K.A. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data: B.N. and K.A. Drafting of the manuscript: B.A. and K.A. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: B.A., K.A., and B.N. All authors contributed to reading and approving the final manuscript

Data availability statement

Due to the restrictions outlined in the participant consent agreement, the datasets generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly accessible. Nonetheless, they may be made accessible by the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Full-Text: (34 Views)

Introduction

Violence refers to any physical or non-physical action against individuals or property (1) that results in harm, irrespective of its legal status (2). These intentional acts of violence can be categorized into three main types: Physical, psychological, and sexual (2). A specific form of violence is domestic or intimate partner violence (IPV), which is perpetrated by a current or former partner (3,4). Research suggests that the motivations for committing IPV are similar across genders, including a desire for revenge, emotional expression, seeking attention, and establishing power and control. Common factors like jealousy, infidelity, anger, and retaliation are cited as shared motives for both genders. While self-defense may be a justification, highly masculine males may face challenges in admitting to such actions (5).

Violence is a significant global health risk that impacts both males and females (4). Its negative effects extend beyond the immediate victims to their families, colleagues, and the wider community, resulting in physical and psychological harm, reduced quality of life, and decreased productivity (3). Victims frequently experience a wide array of physical, psychological (5), and reproductive health issues (6). Furthermore, they may face difficulties in fulfilling their responsibilities, such as caring for children, managing household tasks, and maintaining effective job performance (5).

Given the well-documented adverse effects of domestic violence, its reduction is a critical priority for both public health and sustainable development. A significant concern is that the key indicator for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) measures the prevalence of violence as "the total number of persons who have been a victim of physical, psychological, or sexual violence in the previous 12 months, expressed as a share of the total population." This metric underscores the urgent need for intervention to address violence and promote a safer, healthier future for all (2).

Domestic violence is a universal issue that transcends racial, age, gender, cultural, socioeconomic, educational, religious, and geographic boundaries (3). A systematic review of 366 studies, which surveyed 2 million females from 161 countries, covering 90% of female gender worldwide, found that 27% of ever-partnered females aged 15-49 have experienced physical or sexual IPV in their lifetime. Additionally, 13% of females reported experiencing such violence in the year prior to the survey (7). Despite the fact that domestic violence can be mutual or one-sided (Both female-to-male partner violence [FMPV] and male-to-female partner violence [MFPV]), the prevalence of violence against males has not yet been investigated (8).

While domestic violence against males is a topic that warrants greater attention, it is often overlooked and not taken seriously, culminating in significant underreporting. This issue is largely driven by societal attitudes and perceptions that influence how people view the gender roles of both the victim and the perpetrator. Research indicates that the overall prevalence of partner abuse, including cases where males are the victims and females are the perpetrators, is comparable to instances of male-perpetrated abuse against females (5). Despite the existence of both mutually violent relationships and one-sided cases, such as FMPV and MFPV, the prevalence of violence against males has not yet been investigated (8). Thus, it is highly probable that healthcare providers will encounter patients who are survivors of domestic or family violence (3). Traditional gender-based models of IPV often portray males as aggressors and females as vulnerable victims. However, domestic violence is a complex issue that impacts both genders. A lack of sufficient research on violence within both male and female populations has hindered the ability to draw definitive conclusions (5). Consequently, this study aims to examine the prevalence of domestic violence in both males and females by analyzing the frequency of violent events from the perspectives of both perpetrators and victims.

Methods

The current cross-sectional study was conducted on a sample of 240 couples from Gorgan, Iran, between June and December 2022. Participants were selected from comprehensive health centers and included females aged 20-49 and their spouses. Inclusion criteria required couples to have been married for at least two years, cohabiting, and possessing both a smartphone and internet access. Exclusion criteria included individuals with known physical or mental health conditions, as well as pregnant or postpartum females.

Based on a pilot study of 16 eligible couples (32 individuals), the required sample size for this study was determined. For estimating the prevalence in both males and females, a sample of 234 people was estimated (P = 18.75, confidence level [CL] = 0.95). Furthermore, to calculate the correlation coefficient (r) of violence between couples, a sample size of 240 couples was determined (r = 0.21, CL = 95%, power = 0.80). As the larger sample size was needed for the correlation analysis, 240 couples were selected as the final sample size for the study.

.PNG)

The data were collected after receiving approval from the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Golestan University of Medical Sciences.

The cohort of eligible individuals was initially identified using data from the Statistical Center of the Deputy of Health of Golestan Province. From this list, a simple random sampling method without replacement was employed to select the study participants. This process was facilitated using R software, version 4.4.2. Subsequently, all selected participants, both female and male, were individually contacted through either phone calls or Short Message Service (SMS). Couples who consented to participate and signed the online consent form were subsequently provided with a link to complete the survey instruments independently. The study observed a non-response rate of 20.2%. Both the consent form and the study questionnaires were developed and administered using Porsline (Online survey software). Participants were explicitly instructed to complete the questionnaires individually, without consultation with their partner, to ensure the validity and independence of their responses.

Research instruments included a demographic-reproductive questionnaire for females, a demographic form for males, and the Persian version of the self-report Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2) developed by Strauss et al. Both females and their husbands completed these tools independently.

A demographic questionnaire was utilized to collect data from both male and female participants. The variables included education level, occupation, ethnicity, substance use, pregnancy history, childbearing, abortion, child mortality, and number of pregnancies, live births, and stillbirths.

Based on the conflict theory proposed by Adam in 1965 (9,10), the CTS and its revised version, the CTS2, were developed by Strauss et al. in 1973 and 1996, respectively. These instruments are noteworthy for their ability to simultaneously measure both perpetration and victimization of domestic violence. The CTS2 is divided into two sections of domestic violence and negotiation, and it has been widely applied in various contexts (11). The CTS2 is comprised of 78 items, with an alternating structure where even-numbered questions address the perpetrator and odd-numbered questions pertain to the victim. For a complete assessment, each couple responds to 39 odd items (33 perpetrator items and 6 negotiation items) and 39 even items (33 victim items and 6 negotiation items). Separate scores are then computed for the victim, perpetrator, and negotiation subscales (9).

The original CTS2 showed strong internal consistency, with reliability ranging from 0.79 to 0.95. Its conceptual and methodological validity has also been confirmed (9). For the Iranian population, the Persian version of the CTS2 has been validated as a reliable and effective research instrument. A study by Panaghi et al. (2011) involving 395 participants (206 females, 189 males) reported that the Persian version possesses satisfactory reliability and factor structure, with Cronbach's alpha values ranging from 0.66 to 0.86 (12). The time required to complete the CTS2 is approximately 10 to 15 minutes (9,11).

To assess the prevalence of domestic violence, the CTS2 can be scored dichotomously. A score of 1 indicates the occurrence of any violence, while a score of 0 signifies its absence. Additionally, the frequency of domestic violence across four sub-domains-psychological aggression, injury, sexual coercion, and physical assault-is quantified using a scale ranging from 0 to 7. Within this scale, categories 1 and 2 correspond to one and two occurrences of an incident, respectively, within the past year. For response categories 3 to 5, the midpoint was used for scoring. Specifically, category 3 (3-5 times) was coded as 4, category 4 (6-10 times) as 8, and category 5 (11-20 times) as 15. Category 6, which indicates more than 20 instances, was assigned a score of 25. A score of 0 was given for category 7, indicating no abuse in the preceding year. The scoring for the negotiation scale (0-25) followed the same methodology as the CTS2 (9).

The statistical analysis for this study was conducted using R software, version 4.4.2. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages, were utilized to summarize the demographic and reproductive characteristics of the couples. The prevalence of domestic violence and its various types was then evaluated using frequencies, percentages, and confidence intervals (CIs). In this study, the CIs for proportions were calculated using a specific formula appropriate for situations where the population variance is unknown. The independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis H test was utilized to compare the mean scores of domestic violence and its subscales between individuals identified as victims and perpetrators over the past year, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

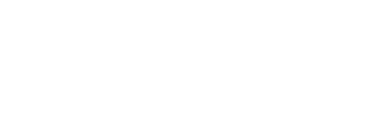

This study involved a sample of 480 individuals, equally divided between males and females (n = 240 per group) (Figure 1). The participants’ education levels were notable, with the majority of both males (71.2%) and females (59.1%) holding university degrees. The majority of females were housewives, while less than 4% of males were unemployed. The sample was predominantly of Persian ethnicity. Regarding economic status, approximately 20.4% of females and 18.8% of males described their family's financial status as inadequate. Furthermore, males reported a significantly higher prevalence of alcohol, hookah, and cigarette use (55%) compared to females (26%). The mean marriage duration for the participants was 13 years (Table 1).

The findings reveal that 52.08% of couples (95% CI: 40.72-58.45) surveyed had experienced domestic violence in the past year. The most prevalent form was unidirectional violence, which accounted for approximately 27% of all cases (95% CI: 10.52-34.70). This was further broken down into MFPV at 19.58% (95% CI: 14.53-26.64) and FMPV at 7.50% (95% CI: 4.14-10.86). Bidirectional violence occurred in 25% of couples (95% CI: 19.48-30.52). Overall, the reported incidence of domestic violence was 32.5% for males (95% CI: 26.53-38.47) and 44.58% for females (95% CI: 38.25-50.92) when combining unidirectional and bidirectional violence (Table 2).

Violence refers to any physical or non-physical action against individuals or property (1) that results in harm, irrespective of its legal status (2). These intentional acts of violence can be categorized into three main types: Physical, psychological, and sexual (2). A specific form of violence is domestic or intimate partner violence (IPV), which is perpetrated by a current or former partner (3,4). Research suggests that the motivations for committing IPV are similar across genders, including a desire for revenge, emotional expression, seeking attention, and establishing power and control. Common factors like jealousy, infidelity, anger, and retaliation are cited as shared motives for both genders. While self-defense may be a justification, highly masculine males may face challenges in admitting to such actions (5).

Violence is a significant global health risk that impacts both males and females (4). Its negative effects extend beyond the immediate victims to their families, colleagues, and the wider community, resulting in physical and psychological harm, reduced quality of life, and decreased productivity (3). Victims frequently experience a wide array of physical, psychological (5), and reproductive health issues (6). Furthermore, they may face difficulties in fulfilling their responsibilities, such as caring for children, managing household tasks, and maintaining effective job performance (5).

Given the well-documented adverse effects of domestic violence, its reduction is a critical priority for both public health and sustainable development. A significant concern is that the key indicator for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) measures the prevalence of violence as "the total number of persons who have been a victim of physical, psychological, or sexual violence in the previous 12 months, expressed as a share of the total population." This metric underscores the urgent need for intervention to address violence and promote a safer, healthier future for all (2).

Domestic violence is a universal issue that transcends racial, age, gender, cultural, socioeconomic, educational, religious, and geographic boundaries (3). A systematic review of 366 studies, which surveyed 2 million females from 161 countries, covering 90% of female gender worldwide, found that 27% of ever-partnered females aged 15-49 have experienced physical or sexual IPV in their lifetime. Additionally, 13% of females reported experiencing such violence in the year prior to the survey (7). Despite the fact that domestic violence can be mutual or one-sided (Both female-to-male partner violence [FMPV] and male-to-female partner violence [MFPV]), the prevalence of violence against males has not yet been investigated (8).

While domestic violence against males is a topic that warrants greater attention, it is often overlooked and not taken seriously, culminating in significant underreporting. This issue is largely driven by societal attitudes and perceptions that influence how people view the gender roles of both the victim and the perpetrator. Research indicates that the overall prevalence of partner abuse, including cases where males are the victims and females are the perpetrators, is comparable to instances of male-perpetrated abuse against females (5). Despite the existence of both mutually violent relationships and one-sided cases, such as FMPV and MFPV, the prevalence of violence against males has not yet been investigated (8). Thus, it is highly probable that healthcare providers will encounter patients who are survivors of domestic or family violence (3). Traditional gender-based models of IPV often portray males as aggressors and females as vulnerable victims. However, domestic violence is a complex issue that impacts both genders. A lack of sufficient research on violence within both male and female populations has hindered the ability to draw definitive conclusions (5). Consequently, this study aims to examine the prevalence of domestic violence in both males and females by analyzing the frequency of violent events from the perspectives of both perpetrators and victims.

Methods

The current cross-sectional study was conducted on a sample of 240 couples from Gorgan, Iran, between June and December 2022. Participants were selected from comprehensive health centers and included females aged 20-49 and their spouses. Inclusion criteria required couples to have been married for at least two years, cohabiting, and possessing both a smartphone and internet access. Exclusion criteria included individuals with known physical or mental health conditions, as well as pregnant or postpartum females.

Based on a pilot study of 16 eligible couples (32 individuals), the required sample size for this study was determined. For estimating the prevalence in both males and females, a sample of 234 people was estimated (P = 18.75, confidence level [CL] = 0.95). Furthermore, to calculate the correlation coefficient (r) of violence between couples, a sample size of 240 couples was determined (r = 0.21, CL = 95%, power = 0.80). As the larger sample size was needed for the correlation analysis, 240 couples were selected as the final sample size for the study.

.PNG)

The data were collected after receiving approval from the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Golestan University of Medical Sciences.

The cohort of eligible individuals was initially identified using data from the Statistical Center of the Deputy of Health of Golestan Province. From this list, a simple random sampling method without replacement was employed to select the study participants. This process was facilitated using R software, version 4.4.2. Subsequently, all selected participants, both female and male, were individually contacted through either phone calls or Short Message Service (SMS). Couples who consented to participate and signed the online consent form were subsequently provided with a link to complete the survey instruments independently. The study observed a non-response rate of 20.2%. Both the consent form and the study questionnaires were developed and administered using Porsline (Online survey software). Participants were explicitly instructed to complete the questionnaires individually, without consultation with their partner, to ensure the validity and independence of their responses.

Research instruments included a demographic-reproductive questionnaire for females, a demographic form for males, and the Persian version of the self-report Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2) developed by Strauss et al. Both females and their husbands completed these tools independently.

A demographic questionnaire was utilized to collect data from both male and female participants. The variables included education level, occupation, ethnicity, substance use, pregnancy history, childbearing, abortion, child mortality, and number of pregnancies, live births, and stillbirths.

Based on the conflict theory proposed by Adam in 1965 (9,10), the CTS and its revised version, the CTS2, were developed by Strauss et al. in 1973 and 1996, respectively. These instruments are noteworthy for their ability to simultaneously measure both perpetration and victimization of domestic violence. The CTS2 is divided into two sections of domestic violence and negotiation, and it has been widely applied in various contexts (11). The CTS2 is comprised of 78 items, with an alternating structure where even-numbered questions address the perpetrator and odd-numbered questions pertain to the victim. For a complete assessment, each couple responds to 39 odd items (33 perpetrator items and 6 negotiation items) and 39 even items (33 victim items and 6 negotiation items). Separate scores are then computed for the victim, perpetrator, and negotiation subscales (9).

The original CTS2 showed strong internal consistency, with reliability ranging from 0.79 to 0.95. Its conceptual and methodological validity has also been confirmed (9). For the Iranian population, the Persian version of the CTS2 has been validated as a reliable and effective research instrument. A study by Panaghi et al. (2011) involving 395 participants (206 females, 189 males) reported that the Persian version possesses satisfactory reliability and factor structure, with Cronbach's alpha values ranging from 0.66 to 0.86 (12). The time required to complete the CTS2 is approximately 10 to 15 minutes (9,11).

To assess the prevalence of domestic violence, the CTS2 can be scored dichotomously. A score of 1 indicates the occurrence of any violence, while a score of 0 signifies its absence. Additionally, the frequency of domestic violence across four sub-domains-psychological aggression, injury, sexual coercion, and physical assault-is quantified using a scale ranging from 0 to 7. Within this scale, categories 1 and 2 correspond to one and two occurrences of an incident, respectively, within the past year. For response categories 3 to 5, the midpoint was used for scoring. Specifically, category 3 (3-5 times) was coded as 4, category 4 (6-10 times) as 8, and category 5 (11-20 times) as 15. Category 6, which indicates more than 20 instances, was assigned a score of 25. A score of 0 was given for category 7, indicating no abuse in the preceding year. The scoring for the negotiation scale (0-25) followed the same methodology as the CTS2 (9).

The statistical analysis for this study was conducted using R software, version 4.4.2. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages, were utilized to summarize the demographic and reproductive characteristics of the couples. The prevalence of domestic violence and its various types was then evaluated using frequencies, percentages, and confidence intervals (CIs). In this study, the CIs for proportions were calculated using a specific formula appropriate for situations where the population variance is unknown. The independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis H test was utilized to compare the mean scores of domestic violence and its subscales between individuals identified as victims and perpetrators over the past year, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

This study involved a sample of 480 individuals, equally divided between males and females (n = 240 per group) (Figure 1). The participants’ education levels were notable, with the majority of both males (71.2%) and females (59.1%) holding university degrees. The majority of females were housewives, while less than 4% of males were unemployed. The sample was predominantly of Persian ethnicity. Regarding economic status, approximately 20.4% of females and 18.8% of males described their family's financial status as inadequate. Furthermore, males reported a significantly higher prevalence of alcohol, hookah, and cigarette use (55%) compared to females (26%). The mean marriage duration for the participants was 13 years (Table 1).

The findings reveal that 52.08% of couples (95% CI: 40.72-58.45) surveyed had experienced domestic violence in the past year. The most prevalent form was unidirectional violence, which accounted for approximately 27% of all cases (95% CI: 10.52-34.70). This was further broken down into MFPV at 19.58% (95% CI: 14.53-26.64) and FMPV at 7.50% (95% CI: 4.14-10.86). Bidirectional violence occurred in 25% of couples (95% CI: 19.48-30.52). Overall, the reported incidence of domestic violence was 32.5% for males (95% CI: 26.53-38.47) and 44.58% for females (95% CI: 38.25-50.92) when combining unidirectional and bidirectional violence (Table 2).

.PNG) Figure 1. Flowchart of study procedure Table 1. Basic characteristics of couples and distribution frequency of domestic violence during the past year (n = 480; Male = 240, Female = 240) .PNG) M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation, Min: Minimum, Max: Maximum * Not good at all (Needs help from benefactors), Not good (Ability to buy necessities of life with a lot of work and loans), Moderate (The ability to buy the necessities of life in the usual way, Good (Ability to buy most items), Very good (Able to buy all items). |

The study found that physical abuse (Including both injury and assault) was the least common form of domestic violence. In contrast, psychological aggression (Occurring 11-20 times per year) and sexual coercion (Occurring 6-10 times per year) were the most prevalent forms. In cases of unidirectional violence, sexual coercion [(Male: victim: 2.23 ± 1.66, perpetrators: 2.56 ± 2.08; female: victim: 2.66 ± 2.12, perpetrators: 2.99 ± 1.9)] ranked first and psychological aggression [(Male: victim: 1.53 ± 2.23, perpetrators: 1.71 ± 2.33; female: victim: 2.05 ± 1.85, perpetrators: 2.68 ± 2.21)] ranked the second most common forms of violence. In cases of bidirectional violence, psychological aggression was the most prevalent form [(Male: victim: 3.51 ± 3.19, perpetrators: 5.0 ± 3.48; female: victim: 5.07 ± 3.67; perpetrators: 4.20 ± 4.14)], followed by sexual coercion [(Male: victim: 2.96 ± 2.21; perpetrators: 4.12 ± 2.66; female: victim: 4.18 ± 2.79; perpetrators: 2.61 ± 1.79)] for both victims and perpetrators across both genders. Overall, the findings demonstrate that psychological aggression is the most common form of violence in bidirectional conflicts. The study found a mean psychological aggression score of 5.0 ± 3.48 for male perpetrators and 5.07 ± 3.67 for female victims. These scores imply that females experienced domestic violence 11 to 20 times in the preceding year. Furthermore, the findings indicate that the highest frequency of conflict resolution attempts through negotiation was observed among males who were victims of FMPV (7.73 ± 13.32), females who were perpetrators of FMPV (7.76 ± 12.11), and females involved in bidirectional domestic violence (Table 3).

|

Table 2. Prevalence of domestic violence among couples by violence type (n = 480; Male = 240, Female = 240)

.PNG) Table 3. Comparison of the mean violence and four subscales (0-25) and negotiation (0-25) of couples (Perpetrator and victim) during the past year (n = 480, Male = 240, Female = 240) .PNG) M: Mean, SD: Standard Deviation * Based on the independent-samples or Kruskal-Wallis H test. |

Discussion

This study, conducted in Gorgan, northeastern Iran, investigated the prevalence of domestic violence among couples over the past year. The findings revealed that nearly 50% of couples experienced some form of domestic violence. Specifically, unidirectional violence was reported by more than half of the participants, with a higher prevalence of MFPV (19.6%) compared to FMPV (7.5%). Bidirectional violence was reported in less than 50% of cases. A broader analysis, combining both unidirectional and bidirectional incidents, showed that over the past year, 32.5% of males and 44.6% of females had experienced domestic violence. The prevalence of psychological aggression and sexual coercion was notably higher, whereas the incidence of physical abuse, such as assault and injury, was less frequent.

The study found that 52% of couples had experienced domestic violence in the past year. This finding is a concerning statistic but is notably lower than the 81% prevalence reported in a study in 2018 on the Iranian population (13). This discrepancy could be attributed to a variety of factors, including differences in cultural attitudes, knowledge, demographic characteristics, and reporting behaviors related to domestic violence. Although increased awareness may have contributed to the lower rate observed in the present study, the prevalence remains alarming. Further research is necessary to fully understand domestic violence and to develop effective prevention strategies.

Based on the findings of the current research, 44.6% of females reported experiencing domestic violence. Findings align with a broader body of research that highlights the high prevalence of domestic violence against females globally. For instance, a notable report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicates that approximately one-third of females living with a male partner have been victimized by their cohabitants (4). A study from southern Iran revealed that 64.1% of female participants reported experiencing domestic violence in the preceding year (14). In a broader context, a systematic review conducted in 2023 highlighted the notable variability in the lifetime prevalence of domestic violence across developing countries, with figures ranging from 29.4% to 73.78% (15). Additionally, a meta-analysis focusing on Iranian females estimated the overall prevalence of violence against them to be 58% (16). In Garmsar, Iran, a study revealed that 56.11% of females had been exposed to violence. This finding highlights the significant global variation in domestic violence rates against females, which are shaped by diverse cultural, social, and economic factors (17). Further research conducted in Kerman, Iran, in 2023 utilized the Network Scale-Up method to estimate that the mean rate of domestic violence against females in the region was approximately 44%. However, the visibility of these incidents, when measured through a direct method, was only 33%, indicating that nearly two-thirds go unreported, likely due to the significant stigma associated with the issue (14). Furthermore, in Ethiopia, 33.5% of married females reported experiencing domestic violence within the past year (18). These findings highlight a critical need for sustained global awareness and intervention efforts to combat domestic violence.

In this study, the prevalence of domestic violence among males was reported at 32.5%. A separate study conducted on married Turkish males found that 57% admitted to perpetrating violence against their wives. A significant portion of these males had a history of experiencing domestic violence during childhood and witnessing violence against females in their formative years (19). The experience of witnessing inter-parental violence and being a victim of child abuse were identified as direct contributing factors to their own victimization as adults (20,21). However, scholarly research on domestic violence against males remains scarce. Male victims of IPV often report feelings of shame and confusion, as their experiences contradict conventional societal norms and expectations of masculinity (22).

The prevalence of domestic violence significantly varies by region and type of abuse. A notable finding, derived from direct measurement methods, indicates an annual prevalence of 60.9% for psychological violence. In comparison, the documented rates for physical and sexual violence are 34.7% and 37.7%, respectively (15). A study from Ethiopia reported high rates of domestic violence, with psychological abuse being the most common at 43.8%, followed by physical violence (28.9%) and sexual violence (19.1%) (18). Similarly, research in Southeast Iran found a high annual prevalence of psychological violence (60.9%), alongside physical violence (34.7%) and sexual violence (37.7%) (14). Based on a comprehensive meta-analysis, the prevalence of domestic violence is reported as follows: Physical violence at approximately 25%, psychological or mental violence at 50%, and sexual violence at 20% (16). Furthermore, a systematic review focusing on the Middle East found that psychological abuse was the most prevalent form, with an occurrence rate of 48.6%. Rates of other forms of abuse were also found to be substantial, including physical abuse (28.4%), sexual violence (18.5%), and injury-related violence (18.4%) (23). These results highlight the pervasive nature of domestic violence, especially psychological abuse, and emphasize the critical need for targeted interventions and support systems for affected individuals in various regions.

This study's findings indicate that among couples who experienced violence within a one-year period, less than 50% involved bidirectional violence. The prevalence of MFPV was 19.6%, while FMPV was 7.5%. These results align with the family systems theory, which posits that the behavior of family members is mutually influential (24). They also challenge the conventional view that IPV is exclusively perpetrated by aggressive males against vulnerable females. This stereotype profoundly affects individuals’ decisions to seek help and influences how service providers respond (25). A systematic review revealed that bidirectional violence is the most prevalent form of violence, occurring regardless of an individual's sex or sexual orientation (26). Despite past research indicating that bidirectional violence is a common pattern, there is a lack of understanding regarding how societal stereotypes and attitudes are expressed when both partners in a relationship are simultaneously in the roles of victim and perpetrator (25). This highlights the need for gender-inclusive services tailored to the specific needs of males, requiring greater recognition, awareness, and resource allocation (27). As Houseman et al. observed, violence is a cyclical phenomenon, with victims living in persistent fear of future incidents. It is a universal issue, transcending cultural, racial, religious, and socioeconomic boundaries within intimate relationships. Although couples may desire an end to the violence, such hope is often unfounded (4).

Based on the study's findings, psychological aggression (Occurring 11-20 times per year) and sexual coercion (Occurring 6-10 times per year) were identified as the most prevalent forms of violence. It is crucial to recognize that the cycle of violence often initiates with verbal threats before escalating to physical aggression. Violent incidents are typically unpredictable, and their underlying triggers are frequently obscure. The perpetrator may demonstrate increased judgmental attitudes, irritability, and volatility, ultimately culminating in an explosive phase. During this phase, the victim may try to de-escalate the situation by pacifying the abuser, maintaining physical distance, or engaging in logical reasoning, often with little success. The explosive phase can prompt the victim to take protective measures for themselves and their family, which frequently results in injury. Subsequently, a "honeymoon phase" may occur, during which the victim might seek counseling and medical assistance and may even agree to discontinue legal actions (4).

This study's use of self-administered questionnaires to collect data on domestic violence over a one-year recall period may have introduced recall bias. Additionally, the social stigma associated with family reputation in Iran could lead to the underreporting of domestic violence. While participants completed the instruments separately, the responses of one partner might still have been influenced by the other's awareness or participation in the study.

Conclusion

This study revealed that nearly half of the couples surveyed experienced some form of violence, with males reporting a higher prevalence than females. The most common forms of violence were verbal and sexual. These findings help healthcare professionals enhance their knowledge and improve the implementation of domestic violence prevention and screening programs. Additionally, the results offer valuable insights for policymakers and practitioners seeking to develop effective strategies to prevent and address domestic violence, with a specific focus on household dynamics, roles, and gender. The results also emphasize the importance of acknowledging domestic violence against males and the necessity for targeted screening programs to safeguard their mental health, particularly by sexual health policymakers. Future research is needed to identify effective interventions for reducing domestic violence and fostering healthy relationships.

Acknowledgement

This study is derived from a master's thesis in Midwifery Counseling at the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, titled "Domestic Violence and Resilience in Couples, Gorgan, Iran, in 2022." The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Golestan University of Medical Sciences for their sincere support, the leadership and staff of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery for facilitating the research, and all participating couples.

Funding sources

This study was financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology at Golestan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 112434).

Ethical statement

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.GOUMS.REC.1401.099) on June 12, 2022. The research was conducted in full accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were 16 years of age or older. Online written informed consent was obtained from every participant after providing full explanations on the research objectives, voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participant privacy was protected by ensuring the confidentiality of their data.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: A.S.B., K.A., and B.N. Data collection: K.A. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data: B.N. and K.A. Drafting of the manuscript: B.A. and K.A. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: B.A., K.A., and B.N. All authors contributed to reading and approving the final manuscript

Data availability statement

Due to the restrictions outlined in the participant consent agreement, the datasets generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly accessible. Nonetheless, they may be made accessible by the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Type of study: Original Article |

Subject:

Midwifery

References

1. Boches DJ, Cooney M. What Counts as "Violence?" Semantic Divergence in Cultural Conflicts. Deviant Behav. 2023;44(2):175-89. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

2. Blom N, Fadeeva A, Barbosa EC. The Concept and Measurement of Violence and Abuse in Health and Justice Fields: Toward a Framework Aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Social Sciences. 2023;12(6):316. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

3. Huecker MR, King KC, Jordan GA, Smock W. Domestic Violence. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

4. Houseman B, L. Kopitnik N, Semien G. Florida Domestic Violence. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2023. [View at Publisher] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

5. Domesticviolenceresearch.org. Facts and statistics on domestic violence at-a- glance Domesticviolenceresearch.org; [Available from: https://domesticviolenceresearch.org/domestic-violence-facts-and-statistics-at-a-glance/. [View at Publisher]

6. Purbarrar F, Khani S, Emami Zeydi A, Cherati JY. A review of the challenges of screening for domestic violence against women from the perspective of health professionals. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12(1):183. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

7. Sardinha L, Maheu-Giroux M, Stöckl H, Meyer SR, García-Moreno C. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. Lancet. 2022;399(10327):803-13. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

8. Kolbe V, Büttner A. Domestic Violence Against Men-Prevalence and Risk Factors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(31-32):534-41. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

9. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283-316. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

10. Straus MA. The Conflict Tactics Scales and Its Critics: Evaluation and New Data on Validity and Reliability. Physical Violence in American Families.1990:26. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

11. Chapman H, Gillespie SM. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): A review of the properties, reliability, and validity of the CTS2 as a measure of partner abuse in community and clinical samples. Aggress Violent Behav. 2019;44:27-35. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

12. Panaghi L, Dehghani M, Abbasi M, Mohammadi S, Maleki G. Investigating reliability, validity and factor structure of the revised conflict tactics scale. Journal of Family Research. 2011;7(1):103-7. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

13. Sohanian HM, Faizi I. Description of Domestic Violence in the Iranian Family. Research in Deviance and Social Problems Year:2023;2(6):1-31. [View at Publisher] [Google Scholar]

14. Ahmadi Gohari M, Baneshi MR, Zolala F, Garrusi B, Salarpour E, Samari M. Prevalence of Domestic Violence against Women and Its Visibility in Southeast Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2023;52(3):646-54. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

15. Christaki C, Orovou O, Dagla D, Sarantaki S, Moriati M, Kirkou K, et al. Domestic Violence During Women's Life in Developing Countries. Mater Sociomed. 2023;35(1):58-64. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

16. Dehkordi AH, Heydari H. The Prevalence of Domestic Violence in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Jundishapur Journal of Chronic Disease Care. 2024;14(1):e138870. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

17. Kamalikhah T, Mehri A, Gharibi F, Rouhani-Tonekaboni N, Japelaghi M, Dadgar E. Prevalence and related factors of intimate partner violence among married women in Garmsar, Iran. J Inj Violence Res. 2022;14(3):165-72. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

18. Bekela Gadisa T, Angasu Kitaba K, Gelan Negesa M. Prevalence and factors associated with domestic violence against married women in Mana District, Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia: A community-Based Cross-Sectional study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2022;17:100480. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

19. Bezgin S, Buzlu S. Domestic Violence: Views of Married Men and Factors Affecting Violence. J Community Health Nurs. 2023;40(3):207-18. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

20. You S, Kwon M. Influence of Direct and Indirect Domestic Violence on Dating Violence Victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2023;38(5-6):5092-110. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

21. Kisa S, Gungor R, Kisa A. Domestic Violence Against Women in North African and Middle Eastern Countries: A Scoping Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24(2):549-75. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

22. McLeod DA, Ozturk B, Butler-King RL, Peek H. Male Survivors of Domestic Violence, Challenges in Cultural Response, and Impact on Identity and Help-Seeking Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(2):1397-1410. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

23. Moshtagh M, Amiri R, Sharafi S, Arab-Zozani M. Intimate partner violence in the Middle East region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24(2):613-31. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

24. Milberg A, Liljeroos M, Wåhlberg R, Krevers B. Sense of support within the family: a cross-sectional study of family members in palliative home care. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):120. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

25. Hine B, Noku L, Bates EA, Jayes K. But, Who Is the Victim Here? Exploring Judgments Toward Hypothetical Bidirectional Domestic Violence Scenarios. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(7-8):Np5495-np516. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

26. Machado A, Sousa C, Cunha O. Bidirectional Violence in Intimate Relationships: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(2):1680-94. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

27. Hine B, Bates EA, Wallace S. I Have Guys Call Me and Say 'I Can't Be the Victim of Domestic Abuse: Exploring the Experiences of Telephone Support Providers for Male Victims of Domestic Violence and Abuse. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(7-8):Np5594-np625. [View at Publisher] [DOI] [PMID] [Google Scholar]

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |